Table of Contents

Fit for purpose

In the safety-conscious world of construction, no site is without warning signs that appropriate PPE must be worn. The acronym – now universally understood after the coronavirus crisis – still seems ill-fitting, given the ‘personal protective equipment’ is usually hi-viz overalls and a hard hat.

Until recently, PPE has been a worse fit for some. Only in the last few years has workwear tailored to match the female form been made widely available. Previously, if not actually less safe, women on the site of construction and engineering projects could only have felt even more out of place in their baggy and cumbersome garb.

Such an oversight is typical of male-dominated industries, even the more technologically advanced. NASA infamously had to abort its first all-female spacewalk by US astronauts in 2019 as there was only one woman-sized spacesuit available.1

Back on terra firma, the UK construction industry seems to be walking the talk of gender equality, but progress is slow. We asked six women – three senior managers and three younger women with more recent experience of joining the industry – to give us their perspectives on the challenges and opportunities for a sector still struggling to compete for talent with more glamourous occupations.

Grim sites

In her long career in engineering, Group Head of Excellence at Mott MacDonald, Liz King has seen the trajectory. As a student civil engineer, she worked summer holidays on site.

You had to be pretty thick-skinned. Back then, in the late 70s and early 80s, you were followed by wolf whistles everywhere you went. It was pretty grim, to be honest.

Initially seconded to a national contractor for site experience, King went on to work with Mott MacDonald across sectors, from airfield pavement repairs to nuclear power and water treatment.

For the first 10 years of my career, every time you were new on site, you’d have to go through that process of being accepted. You put up with it. You demonstrated you were competent, and then the whole thing settled down and it’d be normal. I hope that women don’t have to go through that today. But we certainly did back then because it was so unusual to see a woman on site.

Alas, not all the workforce is out of the backwoods yet.

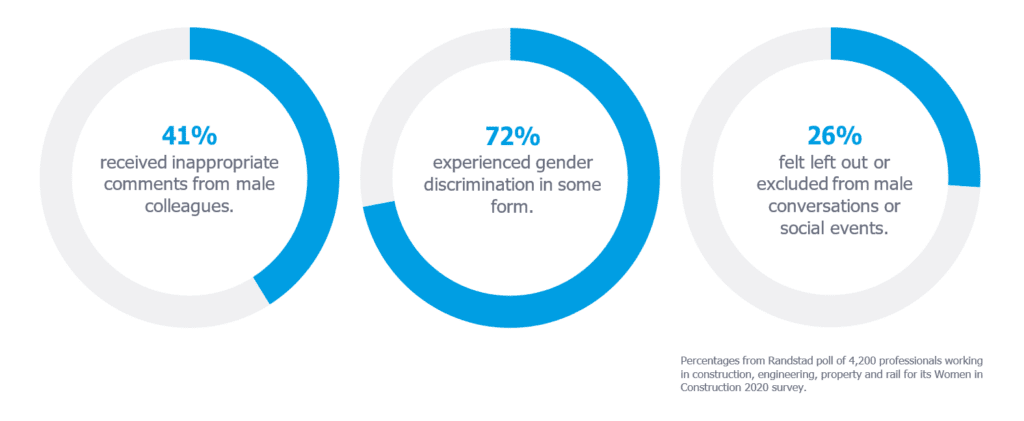

Recruitment consultancy Randstad polled 4,200 professionals working in construction, engineering, property and rail for its Women in Construction 2020 survey.2 Four in 10 female workers (41%) had received inappropriate comments from male colleagues. Almost three quarters (72%) experienced gender discrimination in some form. Of these women, one in four (26%) said they felt left out or excluded from male conversations or social events.

The women we interviewed agree that bias and sexism persist, but tend to be unconscious rather than overt. These manifestations of masculine work culture are especially evident to the newly qualified. Rachelle De Mesa and Flora Cherry each worked 4-5 years in the industry before joining Ayming as consultants.

De Mesa studied civil and structural engineering, before a Masters in Transport Planning & Engineering. As a graduate engineer, she worked in the transport team of an international engineering consultancy.

It was very rewarding, but tough.” As her small gender-balanced group collaborated with other male-dominated teams, “I felt I needed to exert a lot more effort to be acknowledged or even heard as much as any male colleague.

A graduate in civil engineering with architecture, Cherry was the only woman in an engineering consultancy’s team of 12. The company culture was positive, but casual sexism in dealings with contractors and developers was grating: “Who’s the structural engineering guy?” someone asked in a meeting for a residential development. Or the default email greeting: “Afternoon, gents.”

De Mesa relates how female friends were advised by male colleagues: “If you want to do your chartership, don’t get pregnant now, wait until afterwards.”

These experiences may be mild compared with the gauntlet thrown at women pioneers on construction sites. But cultural norms in organisations can make women feel they don’t belong.

“When working in an environment where the interactions are predominantly male it’s quite difficult sometimes to feel that you are part of the club. Other women tell me they feel the same thing,” says King. “The industry’s definitely changing, but it’s still there. And it will be as long as you’ve got a male-dominated industry.”

The ongoing challenge for the industry is not only about increasing the number of women entrants, but also their retention and development, so more advance to senior positions, as Cherry notes. “The industry needs to foster an environment which is attractive to women so they want to stick around, and younger women starting and coming up through the ranks can see the role models are there.”

King agrees: “It’s a great loss to the industry that we can’t retain women after family leave, because the softer skills gained from running a busy household would be of value.”

The battle for equality has to be fought at all levels, Alex Steele, Chief Financial Officer of engineering firm, the Waterman Group, stresses.

There’s a lack of senior women, and construction has fared worse than other industries. But it starts in schools – girls don’t feel they should go into science; there’s an issue at that mid-level stage when working women start to think about having a family; and coming back into the workforce is also a difficult time when we lose quite a lot of women.

Education & training

In schools, lack of awareness of engineering generally, and misconceptions about STEM subjects especially among girls, are still major barriers, as Engineering UK’s research shows (see box A). “A real bugbear of mine is getting young women to do the right examinations,” says Penny Fitzpatrick, Commercial Director of FUSE Architects. “Going into schools and talking to girls about their GCSE options is important so they don’t discount the sciences and maths, and they can go on to become engineers and architects.”

FUSE, Waterman and Mott MacDonald are all active in this effort and related initiatives. The continuing rise in the number of girls taking GCSE physics and computer science is one tentative sign of progress.3

School’s out for engineers

The reasons why most young people don’t consider the construction industry or take relevant courses are complex and it’s not yet clear how to address them, according to Engineering UK. Its 2020 report on educational pathways4 found that:

- Almost half (47%) of 11-19-year-olds said they knew little or next to nothing about what engineers do.

- Just 39% of 14-16-year-olds knew what STEM subjects to study to become an engineer.

- Despite concerted attempts to popularise STEM subjects, girls in particular underestimate their capability, even though they outperform boys at GCSE and A level.

- Even as more students take GCSEs in STEM subjects, entries in design and technology have been falling. Only one in 10 girls takes the subject.

- At A level, boys are still far more likely than girls to study the STEM prerequisites for engineering (61-77%).

- While 60% of girls aged 11-14 think they could become engineers, by 16-19 only a quarter would consider it.5

The yawning gap in young people’s awareness of engineering career options is not being bridged by parents, teachers (given a shortage of STEM-specialists) and patchy careers guidance, according to Engineering UK. Steele, who left accountants PwC to join the Waterman engineering business, sees this as part of a wider societal myopia. “Engineers are not that well respected in the UK,” she says.

As Waterman’s auditor, she was struck by engineers’ straight talking and humility. Attractive traits, they also have a downside. Even though engineers speak with passion about their work, “the industry does not promote itself the way others do,” the chartered accountant explains, citing lawyers and her own profession.

Changing minds and winning hearts is fundamental. “We need to show that there’s fun to be had in this industry, as well as explaining how the subject choices girls make affect their path in further education and careers,” says Fitzpatrick. She advocates more business links with schools, informal internships, and apprenticeships (see below).

Drawing on her experience with PwC’s accountancy apprenticeships and a passion for helping young people from ethnic minorities and disadvantaged backgrounds, Steele helped introduce Waterman’s scheme after the government levy was launched in 2016. “It’s been a huge success. We have diversity in terms of background and some great female apprentices. And we’ve held onto them. This year we will almost double the intake. For me, this is the catalyst to a more diverse workforce.”

Degree-level apprenticeships now offer a second chance for employees who’ve missed out on a university education, but also for companies that cannot attract enough graduate candidates. It’s to be hoped that they talent-spot office staff in clerical or admin jobs – often women – to retrain for harder-to-fill technical roles.

Lowdown on apprentices

Evidence on apprenticeships is mixed, but female apprentices remain a rarity, according to Engineering UK’s analysis for the 2018-19 academic year.

- Overall, the number of apprenticeships dropped after the levy’s introduction, and rose just 5% in 2018-19; (halving in 2020 due to the pandemic).6

- Engineering-related apprenticeships in England followed a similar pattern – rising by 4% year-on-year, but 4% lower than in 2014-15. They accounted for almost a quarter (24%) of all apprenticeships.

- Higher-level apprenticeship starts jumped by 52% compared with the year before, as those at intermediate level fell.

- Women are severely under-represented – with 6% of construction apprenticeship starts in England, 4% in Scotland, 8% in Wales, and 7% in Northern Ireland.

Degrees of progress

One positive trend, though pedestrian, is that more women are studying engineering courses at university or technical colleges. When King graduated, just 5% of her class were female. Including technology courses, the proportion is now 21%.

Across all sectors, 14.5% of those working in engineering occupations are women, according to Engineering UK’s latest analysis (to be published in September 2021) of the Labour Force Survey to September 2020.

Progress is disappointing given the many industry initiatives, not least by WISE (Women in Science & Engineering), in which King was involved. “It would be great to get up to 50%. But in civil engineering, having to work on site can put women off. However, for women who do go into engineering, it’s a much more positive decision – they tend not to fall into engineering the way men sometimes do.”

Other construction professions are faring better.

As with engineering, the number of surveyors has been building slowly – at about 1% a year, so that around 15% of people working in the profession in the UK are women.7 More significant is that almost one in three newly qualified surveyors (31%) are female.

The fading stereotype of the bow-tied architect is not just a sartorial trend. Overall, seven in 10 architects registered in the UK are men, but the gender split is now 50/50 for architects under 30.8

Keeping them is another challenge. “A lot of young women coming into architecture drop out,” says Fitzpatrick. “I think it’s because it’s seven years to qualification and you’re poorly paid.”

The pandemic may have worsened this problem of the ‘leaky pipeline’ as inflexible work demands, childbirth and childcare interrupt or end careers. Research confirms that women continued to shoulder more than their fair share of the domestic burden during lockdowns.

But there’s hope for change on this front too. “Lockdown and working from home will have helped change attitudes about women’s unequal burden of childcare,” Fitzpatrick suggests.

Flexible working could be a game changer this year as we go back to work.

Steele agrees. Greater flexibility on hours and home working could allow women (and their partners) to strike a more equitable work/life balance. “I really hope the industry does take that on board.

King’s career is testament to the benefits for employee and employer. “I always had bosses who understood, and were flexible regarding client meetings or office hours. I worked about 10 years part-time because of childcare. I managed it and the business managed it with me. I’m very grateful and lucky.”

Mentoring women

All see mentoring as essential to keeping women in construction and helping them climb the ladder.

King, who has mentored many over the years, advises upcoming women engineers to find a female mentor. “Having somebody to tap into for advice is helpful: Just asking ‘Is it ok to do this?’ or ‘This happened in a meeting, how do I deal with it next time?’,” she explains.

Steele recently joined a mentoring circle focused on women typically two or more years qualified “who may be grappling with coming back to the industry after children” or blocked in their career.

As a mentor for Future of London network, Fitzpatrick advised young women architects, mainly working for local authorities and housing associations. She’s now part of Forging Links, a group of older women in senior positions trying to help junior architects. “One of the low points as the only woman in the room – in an industry full of acronyms – is not knowing what people are talking about.” The group unpicks topics in an informal environment and language all can understand.

Young women are prey to imposter syndrome while “men are better at winging it,” Steele agrees. They need support, but also resilience, Fitzpatrick explains:

It’s quite often the case you have to soul-search, dig deep and readjust your expectations, after taking a bit of a battering from a contractor or whoever. You tend to get a lot of shouty men in our industry. It’s fraught with emotion because you’re dealing with contract sums, overruns, profitability, and then you’ve got residents to consider.

Being mentored by male line managers who lacked time or passion for the job was a dispiriting experience for De Mesa as a young engineer. “I started reaching out externally to female engineers, and they were willing to make the time for me, because they shared a passion for the work,” she recalls.

Cherry believes some firms are too focused on immediate financial returns to see the benefits of developing a diverse senior team in the long run.

The diversity dividend

The young engineer’s work was heavily focused on 3D structural analysis. Cherry says her major motivation for leaving the industry was the desire to collaborate with a wider range of people and a bigger team. Advising on R&D tax credits means retaining a strong connection with the industry, her colleague De Mesa points out. “You’re still working with engineers and construction professionals, helping them to be rewarded for their hard work”.

Having female line managers and role models is “inspiring and motivating because you see yourself in that position,” Cherry adds.

Across the economy, more women are getting into the boardroom. The number of female directors in the UK’s 350 top companies increased by 50% over the last five years. In January 2021, almost a third of FTSE 100 companies had hit the 33% target set by the government’s Hampton-Alexander Review. However, an earlier analysis by WISE showed that STEM companies were over-represented among the index’s poor performers in 2019, and only one in six (16%) met the 33% target for “women in executive committee members and direct reports”.9

There’s an opportunity cost for construction companies that fail to build diverse management teams. A growing body of research backs the view that diversity drives innovation and raises corporate performance.

Steele emphasises that it’s diversity of thought, as much as gender, that’s key. “With a gender balance, you’re more likely to get that diversity of thinking, but also with different cultures and backgrounds. I do believe that’s vital in decision- making.”

She’s seen it in board meetings with directors of Waterman’s Japanese parent company. Despite Japan’s patriarchal society, their collaborative approach respects all views – “a more female trait that allows everyone to have a voice”.

King agrees that women leaders tend to show “much more willingness to involve their team, communicate and give them the opportunity to voice their ideas and suggest innovations”. Women make excellent project managers, but again, she stresses, it’s about ways of thinking and behaviours, and effective male project managers are collaborative too.

Mott MacDonald is seeking to balance its management team with a more rigorous process for appointments including checks against unconscious bias. “We do positively try and promote people from diverse backgrounds, including gender, wherever we can, but only on merit,” she explains. “We’re certainly seeing larger numbers of women in the top grades.” In the UK, more than 30% of staff are women. The female proportion of leaders (14.6%) and management (27.6%) are both up on 2019. “I can see the benefits in collaboration and the way people are sharing information,” she adds.

Given the challenges facing the sector, construction needs a diversity dividend in innovation and productivity, as well as infusion of new blood into an ageing workforce. Modern projects require a diverse skillset – including specialists in digital, social value, and sustainability, not to mention the emerging fields of drones, off-site manufacturing, retrofitting low-carbon energy, and maybe even site robots.

Many of the capabilities that will increasingly be needed to complement technical expertise are as, or more, likely to come from women.

A different pathway

Neha Bhargava is an exemplar, and someone who, in her own words, “wasn’t looking for a construction career, it found me”.

A Politics and Economics graduate, she left university in 2015. Her first job was as an analyst, compiling reports on corporate governance for shareholders. Approached by a recruiter about an analyst’s job on a highway maintenance contract, “My initial reaction was what everyone thinks of – potholes!”

Eager to build transferable skills – “All companies have KPIs” – Bhargava took the three-month contract with Ringway Jacobs, despite “a fair amount of apprehension”. This wasn’t eased at interview by industry jargon and the technicalities involved in the Essex County Council term maintenance contract.

Having established herself as an analyst in the performance team, she soon moved to the company’s contract with Transport for London. This meant more responsibility as Business Analyst, but also delving beneath the KPI figures into operations – “what was happening on the ground and why”.

Just a year and a half later, Bhargava was Network Manager with her own team of staff, and then operatives, as borough operations were added to her remit. And since April 2021, hers is the pivotal role of Contractor’s Plan Manager on sister company Ringway’s new TfL maintenance contract for central London.

Bhargava manages a team of around 30, planning and coordinating all activities, including an emergency control room. In line with the Mayor’s air quality and congestion goals, Ringway’s innovative set-up includes eCargo bikes, electric vehicles and plant, and delivery pods pre-loaded with materials and kit for maintenance crews.

Four years ago, Bhargava would have dismissed the “ridiculous idea” of being responsible for the upkeep of some the world city’s most famous thoroughfares. Echoing the other women, she admits to “an internal monologue when standing in a ‘war room’ or daily briefing with all the supervisors,” adding: “The problem can be as much your own pre-determined ideas as theirs.” Support and informal mentoring from her line managers has been important.

Her role demands resilience, good communication skills and ability to build relationships with client and borough staff, and the wider team, she says. “Don’t underestimate the soft skills – they help everybody else with technical expertise to work together.”

Asked for her advice to other young women, she replies: “Construction isn’t on young people’s radar unless you’re studying engineering. People are pigeon-holed into roles just because of their CV, but it doesn’t have to be like that.”

That advice should also be heeded by the industry, as it rebounds, post pandemic and the Brexodus of European workers, into the challenges of net zero and worsening skills shortages.

Our interviewees agree that this testing agenda also represents a massive opportunity for the industry to re-position construction as a progressive sector committed to sustainable and socially valuable development. In other words, a good fit for young talent (female and male) seeking worthwhile work with real purpose and relevance to their changing world.