Download your free copy today and join the global conversation on innovation and sustainability or scroll down to read now

The most recent edition can be found here

Looking for previous editions?

As seen in:

International Innovation Barometer

2024

Table of Contents

Foreword

by Hervé Amar, President, Ayming Group

The last year has been characterised by near universal economic difficulty. At the same time, the world is fast approaching very clearly defined net zero deadlines, which will require record levels of both short- and long-term investment in climate technologies. The result is that sustainable innovation has become a focal point for government policy around the world.

Our last International Innovation Barometer examined the challenges that the global energy crisis was levelling at businesses and revealed the strategies being developed to reduce energy consumption and dependency on fossil fuels. This year, we go a step further and consider how this challenge relates to broader net-zero goals by exploring the widening intersection between innovation, technology, and sustainability.

As the global community grapples with the consequences of climate change, the urgent transformation of industries, technologies, and mindsets is a clarion call that can no longer be ignored. But under significant economic pressure, greater support will be needed to accelerate sustainable innovation and limit rising temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as set out in the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015.

The findings of this year’s report present an inflection point where innovation is becoming permanently aligned with sustainability.

Innovation is the catalyst of progress. It can be both the cause and the effect of real, lasting change, and it is essential that businesses are given the tools and means to carry out innovation sustainably. At a time when the bottom line is still the primary driver of business, policymakers must find a way to align the innovation process with new financial incentives.

The following chapters break these challenges down and scrutinise the thoughts and doubts of the individuals who make up the global innovation community, and to that end, I hope you find this year’s Barometer an informative and useful resource.

JUMP TO:

Table of contents

Download a copy

Methodology

This report – the fifth annual International Innovation Barometer – builds on our analysis of R&D over the last four years. In June 2023, we surveyed 1,053 R&D and innovation directors, chief financial officers, and chief executive officers, up from 846 last year.

As part of ongoing efforts to ensure each edition of the Barometer improves upon the last [Last year’s International Innovation Barometer 2023 can be downloaded here], certain survey questions have been updated and expanded from those used in previous years to reflect the evolving challenges facing innovation teams. It is explicitly stated in-text where updated language may have impacted year-on-year comparisons.

Analysis is split into three sections, each analysing specific areas of international innovation. The first sets the scene, looking at the growth of innovation and the barriers faced; section two looks at the way businesses can maximise innovation output; and the third section examines the widening intersection between innovation and sustainability.

The data has been analysed by the following members of Ayming’s senior management team:

Respondents were sourced from the 17 countries listed below and were evenly split between seven sectors: automotive, construction, finance, manufacturing, finance, pharma and technology, as well as between large and small businesses.

Summary of key findings

The Global Innovation Boom

- Innovation has become a priority for businesses, with results revealing that 99% of businesses are innovating, 97% have a defined budget for innovation, and 89% have dedicated innovation teams.

- Innovation was ranked as the second biggest priority, cited by 38% of respondents, second only to operational efficiency at 40%.

- 55% of businesses are spending between 6 and 10% of their revenue on innovation, with the average business spending a considerable 6.4%. This reflects a significant increase from 2021 and 2022, when only 16% of organisations reported spending more than 3% of their revenues on R&D.

- The number of respondents that do not have a defined budget for innovation has dropped significantly from 23% in 2022 to just 3% this year.

Maximising Innovation Output

- The number of businesses self-funding their innovation has fallen by 10 points to 40% and has been overtaken as the most popular source of funding by equity/debt funding, which has increased from 23% to 41% since 2022. Similarly, crowdfunding has also significantly jumped from 7% to 26%.

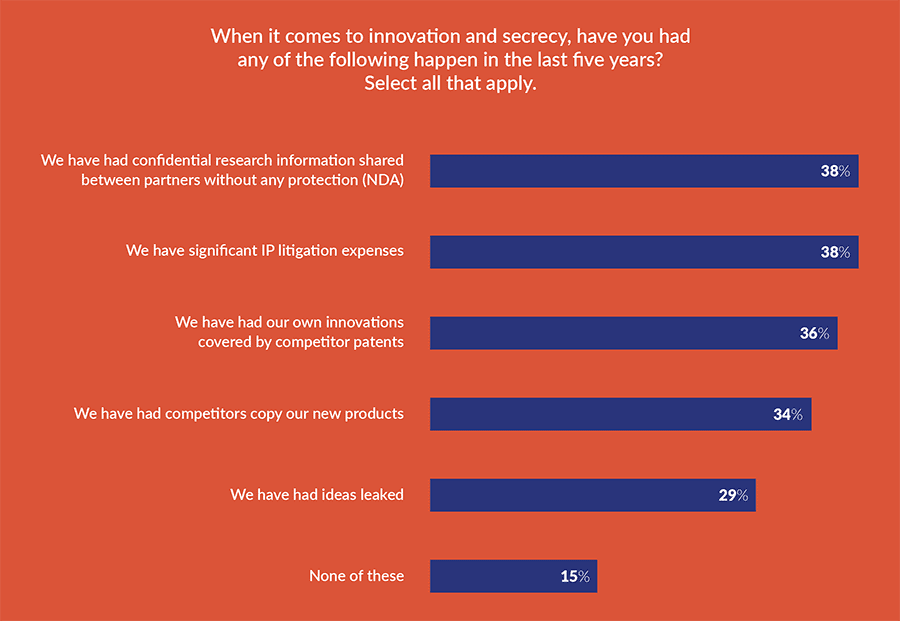

- Strikingly, 85% of businesses have experienced problems with IP conflicts in the last five years, ranging in severity from full-blown corporate espionage to complex cases of intellectual property theft.

- A lack of diversity is also identified as a potential obstacle to maximising innovation output with a global innovation workforce that is just 38% female. Moreover, only 27% of innovation directors are women, suggesting the top jobs are male-dominated.

Innovation’s net-zero destination

- Only 23% of respondents named sustainability as a top-three priority for their organisation.

- However, an emphatic 78% of firms have allocated up to 20% of their annual budget to sustainability, with almost a third assigning between 11% and 20%.

- Investment in sustainability is primarily driven by financial factors rather than ideological opposition, with 47% citing their reasoning as cost savings and efficiency. This is underscored by 41% of respondents who stated their greatest challenge in undertaking sustainable innovation was the high upfront cost and investment required.

- 33% of respondents view insufficient R&D tax incentives and a lack of supportive government policy as challenges to progress.

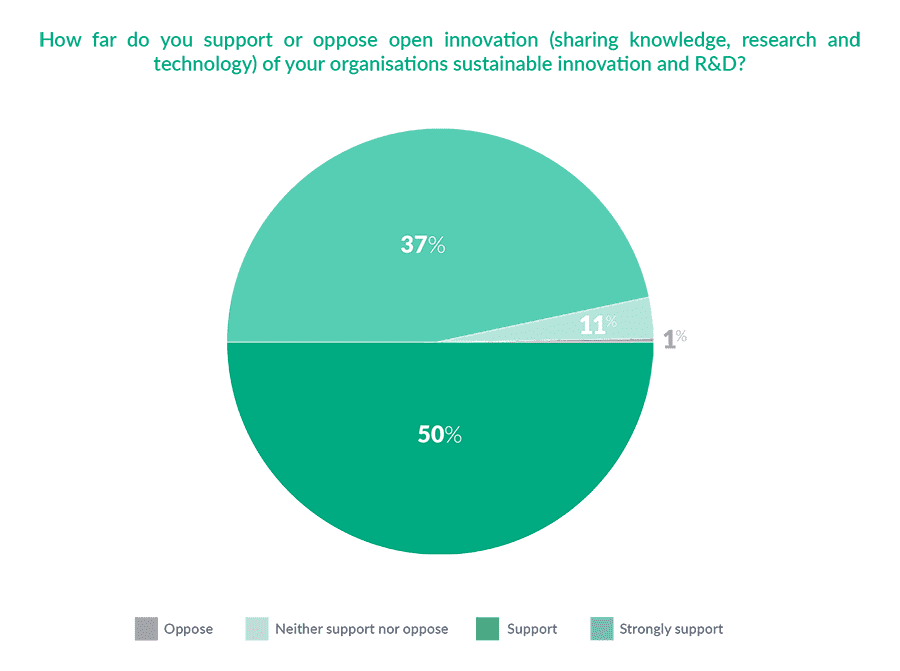

- An unambiguous 87% affirmed that they were in favour of open innovation and knowledge sharing, with 37% declaring themselves to be in strong support.

JUMP TO:

Table of contents

Download a copy

SECTION 1

The global innovation boom

After a somewhat turbulent few years during which projects were put on hold as businesses focused on adapting, innovation is experiencing a resurgence.

Businesses and governments across the world are doubling down on innovation as the global economy edges closer to normality, showing growing awareness of its importance to growth.

The growing priority of innovation

In the five years since the International Innovation Barometer 2020, there’s no doubt that innovation has become a greater priority. Indeed, our research finds that 99% of businesses are innovating, 97% have a defined budget for innovation, and 89% have dedicated innovation teams. That increases to 91% among large firms.

The reality is that you cannot drive competitive advantage without innovation, and it’s clear that businesses recognise that fact despite the economic challenges. Carlos Artal de Lara, Managing Director at Ayming Spain, says, “Every single business leader now recognises that innovation needs to be front of mind. You really can’t put it on the back burner anymore. Whereas before innovation might have been about gaining an edge, it’s increasingly about survival.”

This necessity is reflected in the data. When asked their priorities, our respondents ranked innovation as the second largest priority, at 38%, second only to operational efficiency, at 40% – a huge endorsement. Indeed, innovation is even the third-biggest priority among CFOs and CEOs.

Mark Smith, Partner – Innovation Incentives at Ayming UK, says, “The fact is that most of these objectives are underpinned by innovation. It adds to everything. For example, you can’t enhance operational efficiency without driving innovation. One can’t happen without the other.”

Although the importance of innovation is universal, this enthusiasm is being driven by the automotive sector, which sees it as the biggest priority, whereas energy companies prioritise it the least.

Lauren Fortner, Innovation Manager at Ayming USA, says, “It’s the space race all over again for the automotive industry. The industry has come on leaps and bounds in the last couple of years with the emergence of the popularity of electric vehicles often seen as a status symbol, driving demand for innovation and competition. Unfortunately, we have not seen the same pressures in the oil and gas industry. With a lack of incentives to encourage behaviour changes, the energy industry is prioritising its focus on the bottom line and profitability.”

The flow of funding

These beliefs are translating into action, and businesses are spending a huge portion of their revenues on innovation.

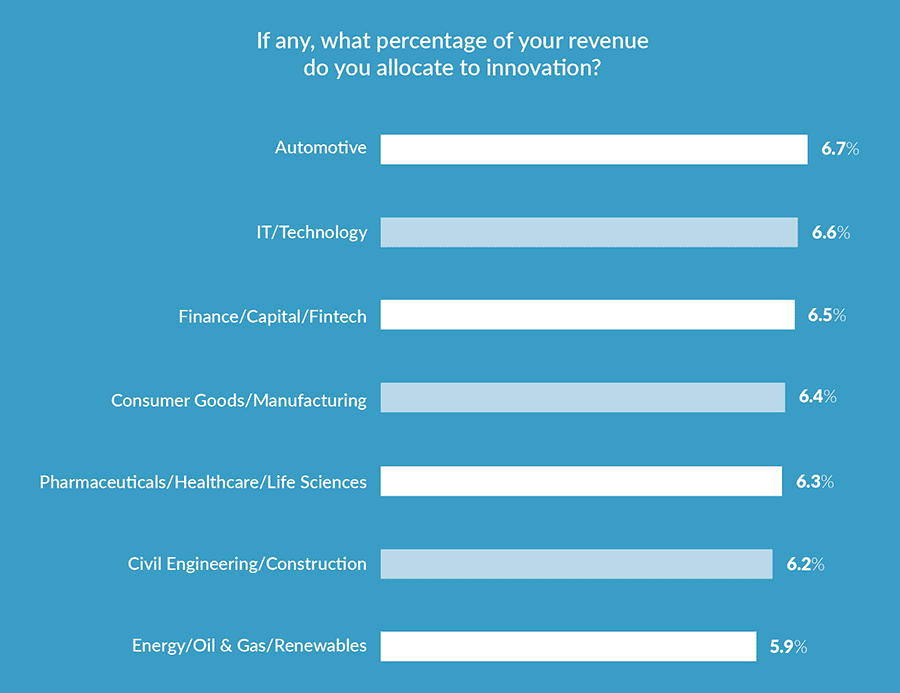

Most organisations are spending 5% or more, with 55% of businesses spending between 6 and 10%. The average business spends a considerable 6.4% of its revenue on innovation, while a miniscule 3% of businesses allocate 2% or less.

Artal de Lara says, “These are vast sums of money. But I think it reflects what’s going on. Companies are seeing the value that their investments bring and are putting more money into them. The more you invest in innovation, the more competitive you are in the market. And in some industries, innovation is critical to a company’s survival.”

This data also shows significant growth compared to previous years. The number of respondents that do not have a defined budget for innovation has dropped significantly from 23% in 2022 to just 3%. In addition, spending seems to have gone up in previous years. Across 2021 and 2022, only 16% of organisations reported spending more than 3% of their revenues on R&D.

That said, it’s important to note the phrasing of the question here, which has changed from previous years and asks about ‘innovation’ as opposed to ‘R&D’. Innovation is broader and therefore captures more, such as later-stage commercialisation, whereas R&D is usually more greenfield and scientific.

Of course, innovation spending can vary massively depending on the nature of the business. Very large businesses (20,000+) are much more likely to spend large percentages on innovation, with 63% spending more than 6%, whereas for businesses of between 10-49 people, the figure is a more modest 39%. Similarly, construction firms are most likely to spend less on innovation, whereas the finance and automotive sectors favour higher percentages.

Supporting the theory that there has been recent growth, most firms report an increase in budgets in the last year, with 69% of businesses reporting increases. 19% say the increase has been significant. Claire Untereiner, Manager – Finance and Innovation Performance at Ayming France, says, “There’s been a big revival recently. 2021 and 2022 were very difficult, but lots of projects have begun to re-launch now that businesses are learning to cope with the impact of the energy crisis. What will be interesting to see is if these figures are the new normal. I suspect they might be.”

The march of technology

A lot of this growth is being driven by the demand for better technology. The data shows that 24% of IT/Technology respondents’ innovation budgets significantly increased. This is because innovation increasingly depends on improving technology, meaning businesses often have to tap into tech companies to support them with their innovation.

Artal de Lara says, “One of our clients is developing a piece of technology for the Spanish Navy. It’s something as simple as a waste disposal system for big ships. Some sectors require technology firms to develop specialised equipment. They help them take a machine closer to perfection, improving processes and costs.”

The growing demand for better technology is reflected in what companies are spending their money on. When asked what their biggest innovation priorities are, implementing new tools and technology was the favourite by some margin, at 34%, with a considerable lead on other options, with researching and understanding customers’ needs and optimising operations, both at 29%.

These findings also echo the overall business objective of enhancing operational efficiency and technology’s role in that. Smith says, “It’s the relentless march of technology. Tools that were once cutting-edge are now standard enterprise solutions.”

Curiously, artificial intelligence is joint sixth, which is a little surprising considering the buzz around AI since the start of the year. Smith says, “I would have expected AI to be higher now, but I think it will be up there in 12 months’ time. You would almost have expected lots of companies to have specifically started new R&D projects to explore AI over the last few months.”

Obstacles to innovation

Although innovation is a priority, businesses inevitably encounter challenges. Many factors, such as the economy, are outside of their control, but companies face a range of barriers from within.

The most common barrier is having a short-term focus and pressure for immediate results, at 38%, which raises the complications of how best to plan innovation. There’s always a juxtaposition between short-term success and building for the future.

Smith says, “The acceleration of innovation cycles does mean businesses have a shorter time horizon for return on investment. If you’re not spending now for the future, it will come back to bite you, so you need a strategy that includes short- and long-term R&D. It’s just about sensible planning.”

The second most common barrier to innovation is the availability of skills and talent, which comes as no surprise. In past Barometers, finding the right talent has featured regularly as a critical challenge. As Njy Rios, Director R&D Incentives at Ayming UK, says, “Innovation is dependent on people.”

It is curious, then, that among the least popular innovation priorities are attracting talent and fostering a culture of creativity. Smith says, “It’s strange that talent is one of the lowest priorities considering the growing complexity of R&D. It’s failing to gain the importance it should.”

It’s possible that people are not focusing on internal talent because they are relying more on external resources, including collaboration or straightforward outsourcing – a topic that we explore in detail in Section Two.

The barriers vary depending on the size and sector of the business. Small businesses, for example, are much more likely to lack skills and talent available (37%) or a clear innovation strategy (34%) compared to larger businesses, which are burdened with inefficient processes and bureaucracy, which also burden the construction sector.

Smith says, “This is often about the size of the project the innovation is helping. HS2 in the UK is a multi-billion-pound project with lots of different companies involved, which comes with communication overheads that can get in the way. It’s much easier for smaller projects.”

Positively, it’s clear that innovation has the support of senior management in most businesses, considering inadequate c-suite support is the least common barrier by some margin, at 25% – 5% below the nearest option.

Smith says, “If you look at company reports, most big businesses have an innovation strategy. A lot of them lead with it. And the introduction of funding and the work to build awareness of R&D funding have played a part in shifting perceptions.”

The important finding here is that businesses overwhelmingly want to innovate. The challenges they face are therefore largely practical and can be addressed to improve output.

Section 1 - Conclusion

There’s no doubt that innovation is working its way up the priority list, which is a trend that looks set to continue in the years ahead. And with more businesses investing in innovation, others will have to follow suit to keep up, creating an innovation growth cycle. But how can companies maximise their innovation output and turn investment into impact? We explore a whole range of ideas in Section Two.

JUMP TO:

Table of contents

Download a copy

SECTION 2

Maximising innovation output

Innovation is not easy. It is a long and complex process going from idea, to experimentation, to commercialisation, and eventually to launch. It rarely goes in a straight line and there will always be challenges and setbacks along the way.

However, businesses can improve their output by being smart with their resources and putting the proper infrastructure in place to improve the performance of their innovation function.

Measuring innovation

In order to improve results, it is first important to understand what is happening. The problem is that measuring innovation is very difficult.

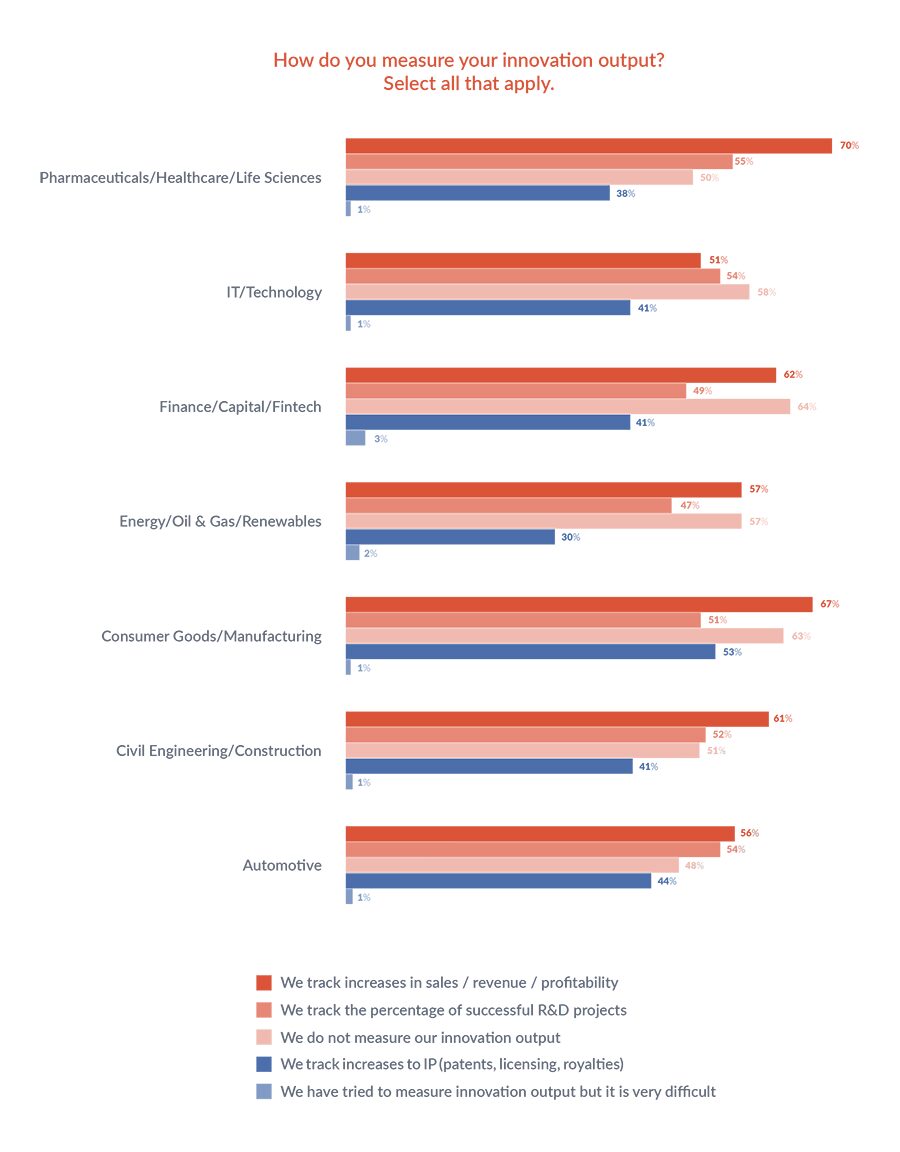

The output varies significantly from project to project, which presents a real challenge to businesses. According to the research, 41% of businesses have ‘tried to measure innovation output but it is very difficult’.

Businesses are most likely to measure innovation by tracking sales/revenue/profits, which 58% of firms do. However, this comes with problems considering revenue will have other contributing factors.

Alternatively, 56% of businesses track the percentage of successful R&D projects. But again, this is not straightforward considering the objective of each project will vary, meaning a business has to set different measurement criteria for each project.

The sectors provide useful examples for the different methods of measuring. For example, consumer goods, which is more likely to focus on creating products, will opt to track sales whereas civil engineering, which is more often looking for incremental improvements and cost reduction, is more likely to track successful R&D projects. Ultimately, measurement has to be established on a case-by-case basis.

Smith says, “The first step has got to be measurement. It’s a challenge but it’s fundamental because if you can measure it, you can improve it. As part of their strategy, innovation departments should set clear objectives for each project. The metrics they use may be different, but it will really support productivity.”

Boosting the budget

When firms are looking to boost their innovation, their first move is likely to increase their budget. Innovation is dependent on having the funding and a lack of financial resources is a leading barrier to a third of businesses.

With economies floundering and costs driven up by inflation, profits are being squeezed making it harder to find the budget internally. This year, 40% of businesses say their innovation is self-funded, which is significantly less than the 50% of firms who were self-funding last year.

This has led companies to look externally for funding. In particular, there has been a surge in equity/debt funding, which has increased from 23% to 41%, overtaking self-funding to become the most popular source of funding.

Untereiner says, “In this day and age, companies know they can’t completely slash their innovation budgets. They know that they need to find the money to make sure that they can still invest, even if they have to give some equity or take out a loan.”

Rising interest rates, however, are making debt funding less attractive, so businesses are likely to favour equity of the two. This explains why crowdfunding has jumped up from 7% to 26%. Untereiner says, “Borrowing is expensive and it’s becoming more difficult to access a loan. That’s why crowdfunding is useful, especially for start-ups.”

However, public funding is also increasingly lucrative as governments channel more money into innovation. R&D tax credits are up on last year as a funding mechanism, from 34% to 37%, but there is still room for growth. Smith says, “R&D tax credits are such a simple form of funding, and it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll receive the money if you are doing the right activity. All businesses should factor it into their innovation plans.”

Grants are also up, with international grants up from 28% to 32%. Artal de Lara says, “Governments are pouring money into grants as they try to encourage companies to invest in strategic areas like AI, clean energy, and advanced medicine. And it’s working. Companies know they can secure a lot of funding if they are successful in their application.”

The best type of funding varies depending on the business. The data shows, for example, that smaller businesses are much less likely to use grants than larger businesses. In fact, smaller businesses are less likely to use all types of external funding and favour self-funding.

Smith says, “This may be a missed opportunity. It’s wise for small businesses to be cautious with how much time they put into grant applications because some are very competitive, and applications are a strain on resources. But there are ways for them to maximise their R&D funding.”

To boost funding, businesses should use external advisers, an approach which has surged in popularity over the last year. Managing applications internally has decreased from 42% last year to 19% this year – less than half than what it was.

The biggest jump in external funding has been in working with accountants, which is now the most common form of support, up from 27% to 57% – a 30% rise. This growth can be explained by the rise in equity/debt funding, which accountants are well-placed to support on. However, specialist R&D consultancies have also jumped up this year from 26% to 42%, showing that companies are exploring public funding opportunities and recognise the abilities of specialists to help them.

Firms must make sure they are using the right experts to increase their budgets. For example, accountants are often not equipped to support with grants because the applications usually require specialist scientific knowledge.

Untereiner says, “In France, there are 300 funds supporting small and medium companies and each of them have their own investment criteria. The public funding landscape is also complex with opportunities arising all the time, so it’s difficult to know what is worth applying for. The assistance of consulting firms, with stronger experience in public funding requirements and higher expertise in impact analyses, increases the success rates of applications three-fold.”

Tapping new resources

While budgets are paramount, it is not as simple as throwing money at the problem. Businesses can maximise innovation output by being efficient with resources and working with external parties.

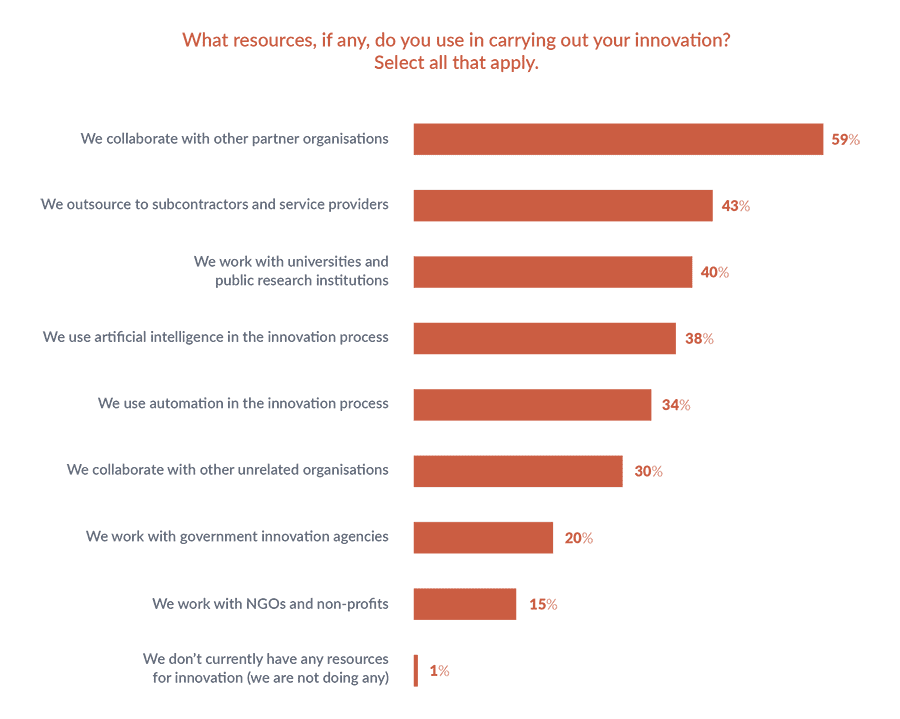

Although collaboration has always been a cornerstone of innovation, it is becoming an increasingly important part of the puzzle. 76% of businesses are carrying out innovation through collaboration – a huge jump from the 37% last year.

Collaborating is a way to leverage other people’s knowledge while also reducing the risk. Fortner says, “If you started a project yourself, you cover all costs whereas if you partner with someone you know and trust, you don’t have to take on all of the financial burden and it increase the chances of successful innovation.”

Artal de Lara argues that the trend towards collaboration is in part being driven by grants, “Grants often favour a consortium. You usually have one large company, which they call a traction company, with a selection of smaller companies that complement the project. The combined knowledge means they are more likely to succeed on the most cutting-edge projects.”

Although collaboration is often preferable, it is not always the best option. The certainty and predictability of outsourcing makes it attractive for certain projects and explains why it is the second most popular resource at 43%. Businesses usually pay a fixed price and have a specific timeline for a project, allowing them to “get it done”, as Fortner says.

The most strategic approach to innovation is to outsource what cannot be done in house or can be done quickly externally. Fortner says, “It’s a way to reach the finish line as quickly and as cheaply as possible. Let’s say a company needs to adjust some software. It wouldn’t make sense to hire 10 programmers and then find something else for them to do when the project is complete.”

IP and innovation espionage

Despite the benefits, working with external parties comes with risks. Intellectual property theft and conflict is very common and fuels huge problems for businesses, big and small.

85% of businesses have experienced problems with IP conflicts in the last five years. The severity of these problems ranges from full-blown corporate espionage to complex cases of intellectual property theft. 34% of respondents have seen competitors copy products and 29% have had ideas leaked.

The unfortunate reality is that security risks can come from a wide range of sources, including partners. Indeed, 38% of companies have shared confidential research information between partners without an NDA.

Businesses should take precautions with their IP, the most obvious of which is patents. But patents are difficult and slow to obtain and – even with one – it can be expensive to benefit from it considering the legal costs. As such, businesses increasingly only take the time to protect innovation if it is truly groundbreaking and gives them a competitive edge.

The automotive sector is particularly cautious and collaborate the least of all sectors in case it leads to leaks in their designs or technologies. This approach appears to work considering the automotive industry had the lowest percentages of each type of breach.

Fortner says, “I have a client that makes parts in the car industry and they have very strict contracts with the manufacturers. They cannot use certain tools on anybody else’s parts even though they’re in their facility. They’re not sharing technology.”

This is perhaps a sensible approach. The impact of having knowledge stolen or copied can be enormous. Not only can you lose your competitive advantage, but it can cause huge litigation expenses, which 38% of businesses have experienced in the last five years, rising to 44% among large businesses.

However, patents are not the only protection. Artal de Lara says, “By the time you have a patent, it’s often outdated. Today, innovation cycles last months instead of years, and we are only going to see that increase with technology like artificial intelligence with quantum computing. So for me, the only way to avoid being copied is to go faster.”

Innovation scouting

The desire to innovate faster has led to the growth of what can be described as “innovation scouting”. Plenty of companies use incubators to fund and support start-ups that are built from inside the company.

However, many companies now search for specialists that are doing innovation that complements their own, working with them and eventually acquiring them as a shortcut to R&D. This is a particularly attractive model for large companies, which helps to explain why large businesses are much more likely to outsource, at 58%, compared to small businesses, at only 38%.

Artal de Lara says, “It’s one of the best ways of innovating. Let’s say you are a pharmaceutical company and there’s a startup that has done in-depth research on drug X. The big firms don’t have the ability to look at all drugs so, instead of taking months to do the research themselves, they partner with that business. And if the research continues to add value, they acquire them.”

This is an increasingly common approach to innovate as quickly as possible. By searching for ideas and R&D abilities from a range of external sources, companies can significantly minimise resources and cut the time to market.

Artal de Lara says, “The key concept here is speed. You may be very quick, but you won’t be as quick as somebody who already has it. It’s no longer just about “how can I innovate?”. It’s a question of going out and seeing what other people are doing, what competitors are doing, and what is going on in the market.”

Innovation scouting like this is also not restricted by location. The niche expertise that companies need are not necessarily going to be local. In fact, they are much more likely to be located abroad.

Offshoring and the battle for innovation

Where to do innovation has long been one of the most critical decisions for businesses. And although there are advantages to keeping the function close to home, the international approach to innovation is growing.

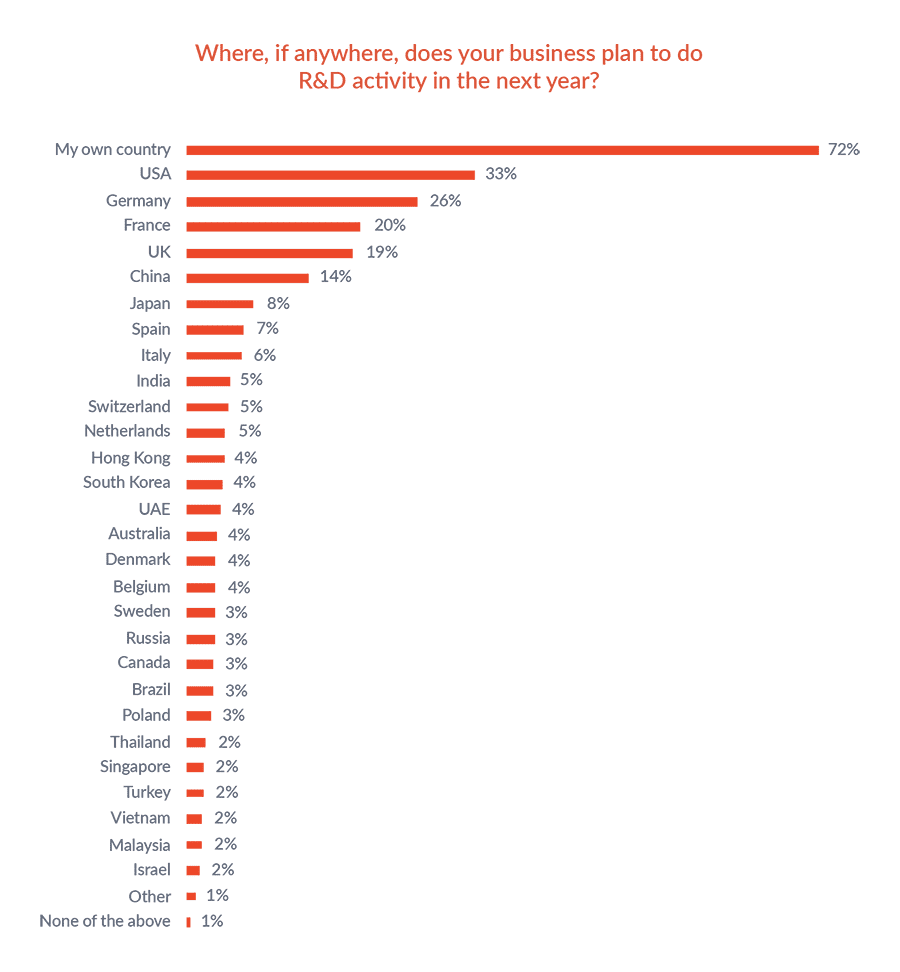

72% of businesses plan to innovate abroad next year. And supporting the innovation scouting theory, the two most common motivations for doing R&D abroad are access to the necessary R&D talent and collaborating opportunities, both at 33%. Clearly, the decision to offshore often hinges on where the expertise is.

Not only can offshoring open access to new pools of knowledge, but it can be cost-effective. For example, 26% of businesses say lower wage costs are their reason for moving activity abroad. Rios says, “For many, it doesn’t matter if they’re in the UK, in Spain, or Thailand. The options have exploded in recent years, especially when the motivation is to outsource, collaborate, or acquire.”

Depending on the situation, business may be looking for something more permanent and establish an R&D department in a specific country.

Almost all countries are aggressively trying to attract innovation opportunities. According to our research, the most popular destination by some margin is the USA, with 33% of businesses planning to innovate there, followed by Germany and France, at 26% and 20% respectively. The UK has slipped down the rankings and is below Germany and France this year, reflecting the exodus of R&D activity from the UK discovered by Ayming’s UK Innovation Barometer.

In terms of what is attracting activity, funding is always an important part of the equation, with grant funding and R&D tax credits in fourth and fifth place as influences. Artal de Lara says, “If you are a UK company, you cannot take advantage of European grants. But if you come and set up an office in Spain, you are entitled to receive all the grants that are available in Spain.”

However, given both types of funding are behind talent and collaboration, expertise is valued more than money. The fact that the USA is the most popular destination supports the view that funding is secondary to talent. Fortner says, “In the US, the R&D credit is not very generous compared to a lot of regions. It’s between 5% and 14% back on your investment. Canada on the other hand provides about 40% back. Instead, the USA offers a huge talent pool and lots of businesses to work with.”

Therefore, from a policymaking standpoint, it is better to create an environment for talent to thrive than it is to provide lucrative funding.

The inevitability of AI

On top of where to do R&D, businesses can leverage tools that can increase output.

The most celebrated of these is artificial intelligence. Since the explosion of Chat GPT earlier this year, many businesses have started exploring how to use generative AI, including for innovation. Currently, 38% of businesses are using AI in the innovation process.

In its most basic form, AI can be used to speed up innovation cycles by supporting innovation teams with sourcing information and drafting reports. However, the elegance of AI is that businesses can use it in the way that suits them, which is why there is such a disparity between sectors. The manufacturing sector uses artificial intelligence in the innovation process more than any other industry at 49%.

Looking ahead, AI is likely to play a major role in innovation. Rios says, “The future of innovation will be AI-driven. It’s still not that sophisticated, but eventually, it will be able to drive forward ideas and facilitate new levels of innovation for innovation teams to carry out.”

Infrastructure and leadership

Although AI is exciting as a resource, companies must make sure they have the right infrastructure in place. For example, 11% of businesses do not have an innovation team. One might expect that to only be small businesses, but the figure is still 9% among businesses with over 250 people.

Rios says, “In this day and age, you should have a dedicated innovation team. There are some things you can’t outsource and, without a team managing it all, you can’t hope to expect your innovation budget to go nearly as far.”

However, businesses should also have certain mechanisms and processes in place. On first glance, it looks like most businesses have everything in place, with businesses overwhelmingly viewing their key internal processes positively.

The area in which businesses are most confident is agile and flexible working practices, which 64% of firms rate “high” or “very high”, which is most likely due to remote working. On the other hand, businesses are least confident about their mechanisms for customer feedback and incubation and commercialisation teams. Smith says, “Good ideas aren’t worth anything if you can’t bring them to market and execute them well.”

Businesses face different challenges depending on their size. Smaller firms are less likely to have effective incubation and commercialisation teams, which they are least likely to rate as “high or “very high”, whereas large businesses face bureaucracy challenges. In fact, inefficient processes and bureaucracy was the biggest barrier to innovation in large businesses.

Smith says, “Size is a natural enemy to innovation. Not only is it harder to maintain that nimble, fail-fast culture, but it’s impossible for everybody to have oversight of what their peers are doing around the business. The R&D team might explore something that doesn’t align with the sales goals.”

That being said, the results raise some eyebrows. Across all of the different mechanisms, only between 2% and 3% of businesses say they do not have them at all, which raises doubts as to whether this confidence reflects the reality.

The cracks begin to show when you look at the data according to job title. Innovation managers/directors consistently rate their practices lower than their CEO and CFO counterparts, suggesting a misplaced optimism. In particular, innovation teams rated incubation and commercialisation highly 51% of the time, compared to CFOs and CEOs who rated them highly 63% and 62% of the time, respectively.

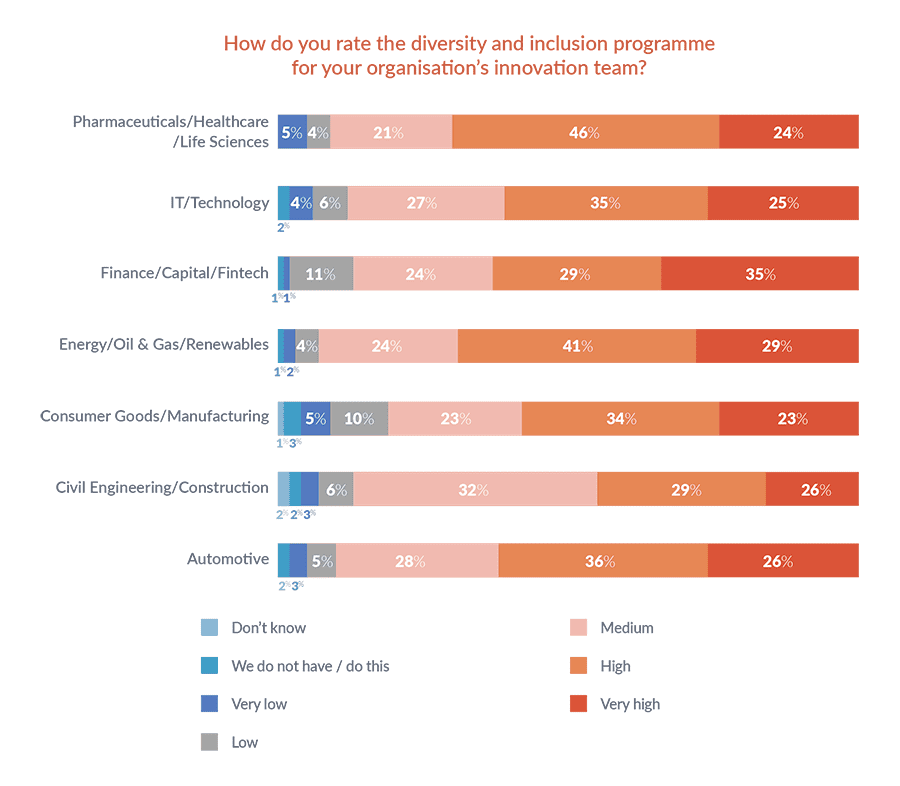

There are some considerable gaps in perspectives here. Business leaders must work closely with innovation teams to find out what works well and implement the right mechanisms. One of the most important is a programme for diversity and inclusion.

The innovation diversity deficit

The impact of diversity on innovation is well documented, which is why it is especially important for innovation teams.

Rios says, “The objective of innovation is to come up with ideas, solve problems, and think differently. You need people from different backgrounds to come up with different answers to the same question. If you don’t have that, you won’t innovate as well.”

People are generally very positive about their diversity programme for their innovation team. 63% rated their programme “high” or “very high” and only 2% of businesses do not have a programme at all.

However, the data tells another story. Only 38% of the global innovation workforce is female and 62% male. In addition, 27% of innovation managers/directors are women, suggesting the top jobs are male dominated. 7% of businesses have no women on their innovation team. These findings are all the more stark when one considers that the average number of people on the innovation team is 111. Rios says, “Even if we can’t have an equal number, we should definitely have representation.”

When we asked whether businesses had representation across a range of traits, 29% had no ethnic diversity, 33% had no diversity of economic background, 63% had no people with disabilities, and 81% had no people that are neurodivergent.

As one would expect, the smaller the businesses and innovation team, the less likelihood of representation, with small businesses much less likely to have any ethnic or neurological diversity.

However, large businesses are perhaps too confident. Even though 67% of large businesses rated the quality of their diversity programmes as either “high” or “very high”, much higher than the 57% for small businesses, one quarter (25%) of large business do not have any ethnic diversity on their innovation team.

Fortner says, “It’s essential to make a concerted effort to recruit from bigger pools. The candidates are out there, it’s just about building relationships with the right places and institutions, which often falls on the HR department. In the US for example, we have HBCUs, which are historically black universities.”

As well as this, 24% of large businesses did not have any neurodivergent (ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, dyslexia) representation in their team, compared to only 13% of small businesses. Fortner says, “My husband has ADHD, so I understand it well. Although it comes with challenges, they really focus on things that really excite them and therefore can be excellent problem solvers. Having a person like that on an innovation team could only be a good thing.”

In terms of a solution, Rios gives her thoughts, “People usually want diversity, but lots of companies simply don’t know how. Realistically, the first step is noticing and identifying problems that start at recruiting. There has to be a concerted effort because it won’t happen by accident.”

Section Conclusion

There is no magic formula for innovation. It is a careful balancing act that requires constant dedication. But it is always possible to make investments go further. At the very least, all businesses should have an innovation strategy, but there are a whole range of approaches and techniques they can deploy that will help them on their innovation journey, whether that is tapping into talent from the other side of the world, leveraging AI, or measuring outputs more effectively. These techniques will become increasingly important as innovation becomes more complex and demanding.

JUMP TO:

Table of contents

Download a copy

SECTION 3

Innovation’s net-zero destination

Over the last year, extreme weather and a global energy crisis have driven governments to push through unprecedented legislation to more urgently address climate change. These policies have ushered in a new era of sustainability-driven innovation – underscored by a broad consensus that climate technology represents the quickest route to achieving net zero by 2050, as outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement.

This chapter will examine the widening intersection between sustainability and innovation and consider how firms can capitalise on the likely future where innovation and net zero strategies are synonymous.

Unsustainable procrastination

Despite new incentives, the international push towards sustainability is yet to be reflected in businesses’ innovation priorities. In fact, sustainability and environmental responsibility ranked as low as sixth, with less than a quarter of firms naming it as one of their business priorities.

This primarily reflects the challenging economic environment, suggesting that sustainability is still viewed as a nice to have as opposed to a lever for commercial growth. Troublingly though, the findings do indicate that there is a gap between intention and implementation. For example, whilst the US government’s Inflation Reduction Act was signed into law in August 2022 with the intention of making sustainability a priority for US businesses, just over one-in-five currently see it as such.

Fortner puts this down to the natural lag that occurs before the value of new policies has filtered down to their intended beneficiaries, stating, “We won’t see attitudes towards sustainability radically shift until businesses have begun to benefit from the measures included within the Inflation Reduction Act. Frankly, until the point that businesses are deriving economic value from prioritising sustainability, it’s never going to rank higher than the likes of ‘increasing market share’ and ‘cost reduction’.”

Budget allocation is also a useful indicator of businesses’ prioritisation and presents a more positive prospect for the long-term. 95% of firms have an allocated budget, with 78% allocating between 1 and 20% of their annual budget to sustainable innovation. Almost a third assign between 11% and 20%.

Rios says, “Businesses are starting to recognise the long-term opportunities sustainable innovation presents. And whilst the short-term investment is high, it looks like the vast majority have a strategy in place to benefit from the relationship between sustainability and efficiency maximisation.”

These seemingly contrary findings reflect the tension between long- and short-term goals. So, whilst the global economy suffers, a clutch of competing priorities will inevitably undermine short-term intentions to prioritise sustainable innovation. But the long-term prospect is positive if budget allocations remain on the trajectory currently set.

The financial sector is allocating the most budget to sustainability with 7% of respondents assigning between 31% and 40% to sustainable activity – two points greater than the average. These findings reflect the pressure the global financial sector is coming under to accelerate the pace of its progress. Having previously been resistant to many of the actions required by the transition, with mainstream consumers now legitimising change on one hand and financial regulators necessitating it on the other, the sector has no choice but to move ahead with greater purpose.

Untereiner suggests that more regulatory requirements should be introduced across other sectors, stating, “In order to see the kind of innovation required to meet rapidly approaching sustainability targets, a balance must be struck between the introduction of new incentives alongside firmer regulatory demands. Incentives, whilst attractive, will only go so far but legislating certain requirements will force the issue.”

This attitude certainly informed the thinking behind the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan. Presented in February 2023, the package of legislation aims to increase the competitiveness of Europe’s industry by creating a more supportive environment for scaling up the continent’s manufacturing capacity of net-zero technologies and crucially, introducing regulations that reinforce this goal.

As more countries introduce policies intended to spur green innovation, aligning businesses’ bottom lines with sustainable activity will be the key to influencing greater prioritisation.

The state of play

Aside from the evolving regulatory environment, investment in sustainable innovation is being driven by a series of factors.

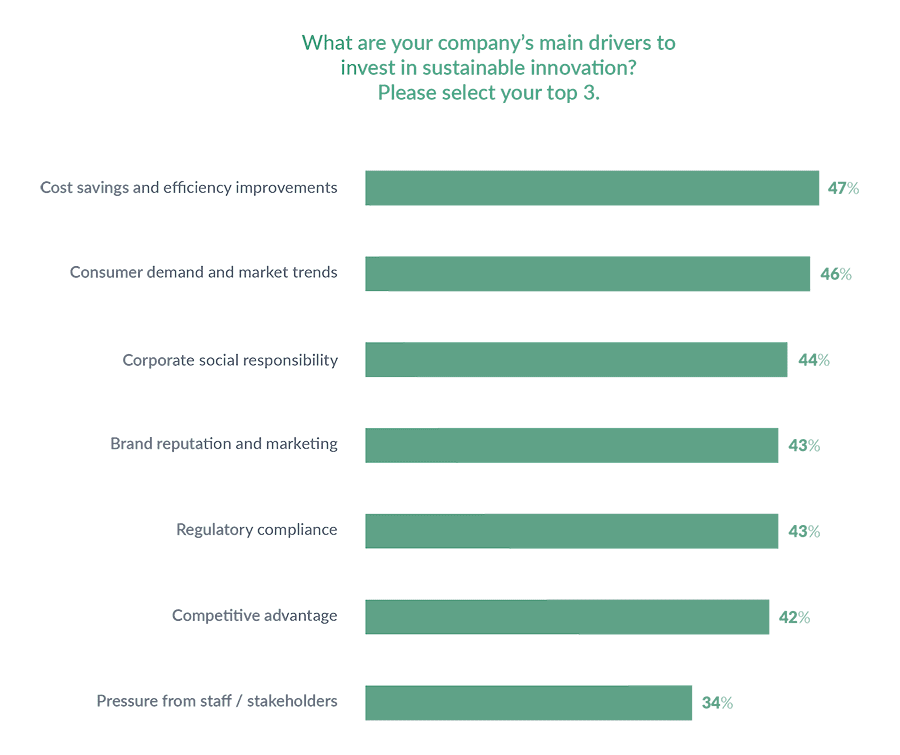

There is not one single driver of change that stands out in the results. Instead, an even spread of results suggests that it’s a combination of several factors that is motivating firms to invest in sustainable innovation.

Just five points separate the first and second-to-last factors with 47% putting their investment down to cost savings and efficiency improvements and 42% citing competitive advantage as their reasoning. 46% of businesses have been spurred to action by consumer demand and market trends, 44% by corporate social responsibility, whilst brand reputation and regulatory requirements were driving factors for 43%.

This data demonstrates that businesses recognise the economic benefits of net zero with just under half opting to invest in sustainable innovation to lower their costs and more than two-in-five using it to gain a competitive advantage over others.

Untereiner reflects, “Businesses see sustainability as more than a marketing slogan. The more that decision-makers are able to see a direct correlation between cost-savings and sustainable innovation, the harder sustainability and innovation will be to distinguish as standalone concepts.”

As the technologies facilitating the transition to net zero become cheaper and the cost curve shifts, businesses can afford to utilise them to spur new cycles of innovation. Much like the industrial revolution of the 18th Century, which was facilitated by the innovation of steam power to increase output by making production processes more efficient – transformation now is being catalysed by new forms of technological innovation. However, the rate of adoption is still too slow to see the large-scale progress required to achieve net zero by 2050.

Artal de Lara says, “Manufacturers of renewable energies have demonstrated that costs can be driven down enough to make sustainable alternatives economically viable for all businesses – the same is just starting to happen with electric vehicles and will soon occur with carbon-free steel. The technology to carry out the transition already exists, but it needs to be deployed at a far greater scale to have a major effect.”

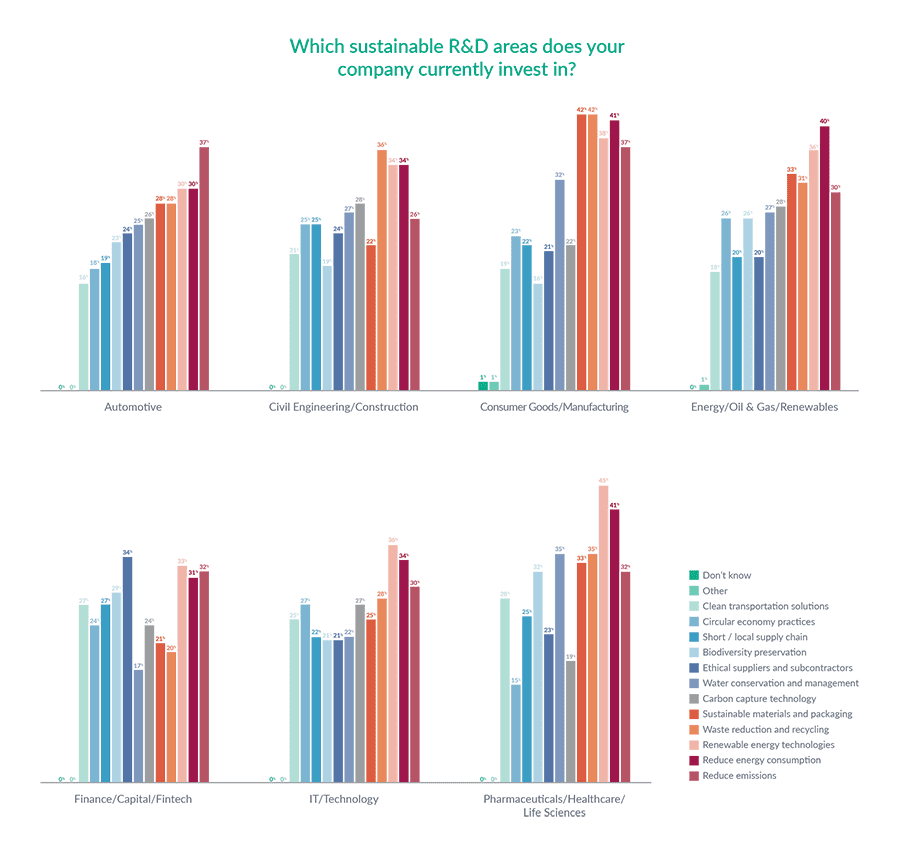

The data also reveals the areas into which investment in sustainable innovation is being directed.

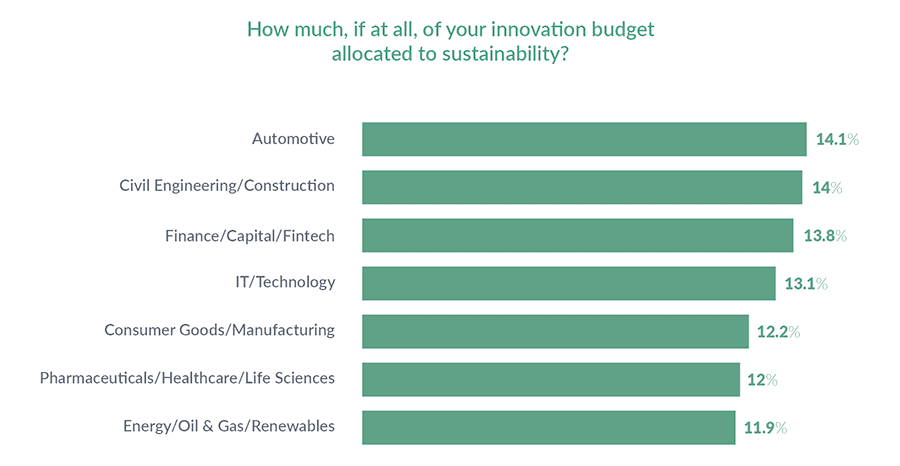

36% of respondents are currently investing in renewable energy technologies and 35% are investing in reducing their energy consumption. Given the turbulence across the global energy sector in the past year, it is not surprising that the two areas receiving the most investment are energy related.

Reducing emissions and waste reduction and recycling also factored highly with 32% and 31% of respondents respectively investing in these processes. The construction sector is investing the least in reducing emissions with only 26% – six points below the average – of the industry funnelling investment towards this goal. As a carbon-intensive industry hyper-aware of its need to reduce emissions, this poses a potential risk to the global sector’s decarbonisation efforts.

Rios puts the finding down to a sector that is still working out how to balance competing priorities, stating, “The construction sector operates on particularly tight margins and maintaining profitability remains a major challenge. Whilst net zero is a primary objective, greater support from government will be required to make the transition successful because no firms in this sector can afford to sacrifice any percentage of their margin to invest in lower-carbon concrete and remain in business.”

The next five categories of investment are separated by just five points. 28% of respondents are investing in sustainable materials and packages, substantially driven by the manufacturing sector, where 42% of respondents are directing investment towards this goal. 26% are invested in carbon capture technology, 25% in water conservation and management, 24% in ethical suppliers and subcontractors and 23% in localising supply chains.

The remit for what constitutes sustainable innovation remains broad and if ambitions to reach net zero by 2050 are to be achieved, progress must be made in each of these channels across every sector.

Clearing the hurdles

Whilst momentum remains positive, significant barriers are preventing businesses from moving ahead at the speed needed to meet climate goals.

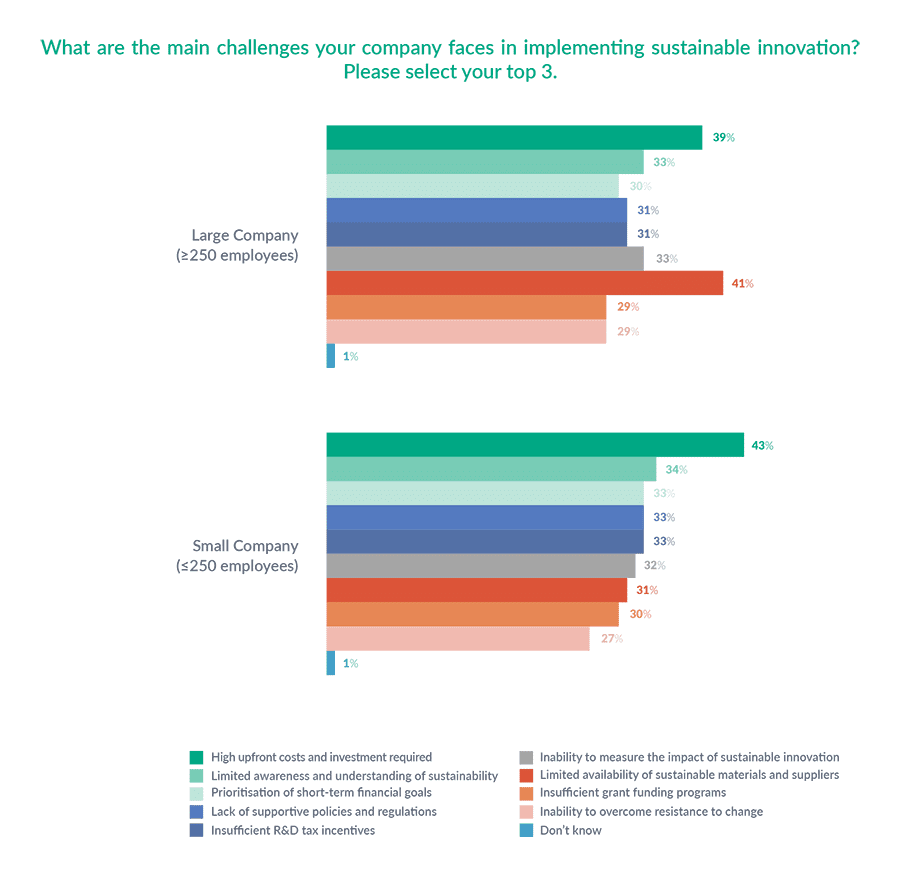

For 41% of respondents, the greatest challenge in undertaking sustainable innovation is the high upfront cost and investment required. The data reveals emphatic consensus across regions and sectors that the barrier to progress is practical rather than ideological, which should inspire some confidence that when additional government resources have filtered down to those carrying out innovation on a day-to-day basis, this challenge can be overcome. This narrative is reinforced by nearly a third of respondents who view insufficient R&D tax incentives and a lack of supportive government policy as challenges to progress. 36% also deem insufficient grant funding programmes a barrier and 31% prioritise short-term financial goals.

Artal de Lara believes this pattern provides a clear directive to political leaders, “Of the nine primary challenges identified, five relate to the need for greater up-front support to address the high cost of initial investment. Governments still waiting to execute on plans to support businesses should need no greater rationale to pass through legislation.”

Beyond the financial barrier, respondents also cite several fundamental obstacles to progress that must be addressed. A third of businesses feel that staff’s limited awareness and understanding of sustainability is holding them back, making a strong case for increasing education. Whilst governments continue to twin the concepts of sustainability and innovation, until there is widespread access to specialist expertise in this area, a gap will always remain. For all innovation to become sustainable, there must first be a common understanding of what constitutes sustainability.

Untereiner says, “In the future, non-sustainable innovation simply won’t exist. But the world is in a race to get to that point before the worst consequences of climate change have occurred, so far more must be done to educate the businesses that are carrying out the day-to-day innovation around the world.”

Another third of businesses point to the inability to measure the impact of sustainable innovation and 36% are concerned about the limited availability of sustainable materials and suppliers whilst 28% cite an inability to overcome resistance to change as a barrier, although this is likely to decrease organically as the evolving landscape forces the issue.

Overcoming this set of barriers in the timeframe required to mitigate the worst impact of climate change will require immense international collaboration. And whilst the concept of knowledge sharing is often seen as controversial, the potential impact for accelerating global progress to net zero is absolutely massive.

Naturally, the obvious challenge with the concept is that businesses might be reluctant to sacrifice their competitive advantage, which has been identified as an important driver for many pursuing sustainable innovation goals.

It’s startling therefore that when faced with the question of how far they would support knowledge sharing of their sustainable innovations, an unambiguous 87% affirmed that they were in favour with 37% declaring to be in strong support. 11% were neutral and just 1% of businesses were in direct opposition.

Rios is sceptical. She says, “It’s great that in principle businesses are keen to collaborate. But that’s not the reality in practice for many. No business will freely give up its intellectual property in a competitive area. However, if there was a way around that commercial restriction, it’s hugely encouraging to know that this concept has such widespread support. Now, we just need that to turn into action.”

Willingness is the crucial takeaway here. For almost 90% of businesses to support open innovation and knowledge sharing, the potential at least to accelerate the timeframe to achieving sustainability targets has been thrown wide open.

Section 3 - Conclusion

The global economy is on the cusp of fundamental change but until policy is translated into practice – where businesses have access to new funding streams – sustainable innovation will continue to be rendered a mid-level priority. Climate tech is consistently positioned as the conduit to take the world to net zero but to generate perceptible change, it must be adopted at scale – and this will require investment. And in the process, the concepts of innovation and sustainability will become indistinguishable as businesses work towards an endpoint where all innovation is sustainable.

JUMP TO:

Table of contents

Download a copy