Table of contents

Introduction

In this report – our second International Innovation Barometer – we take a deep dive into the world of Research and Development (R&D).

It has been a big year for global innovation. The positive rhetoric around R&D has continued to pick up and it is increasingly recognised as the way to push the boundaries, to go further, to anticipate the needs of the customers and to lead markets. In our mind, it is synonymous with economic progress.

For this report, we asked R&D professionals, c-suite executives (including CFOs), and business owners a series of questions, which have provided us with three sections: the first two on The Innovation Landscape and Financing Innovation are the same as last year, allowing us to draw comparisons, whereas this year’s third section focuses on Sustainable Innovation. The findings reveal some striking similarities to last year as well as some key deviations that give us a detailed picture of how the R&D function is evolving over time. As ever, the pace of change is fast, with new trends, new challenges and new technologies emerging.

Although global lockdown is likely to have presented problems for some R&D professionals who have not been able to access their sites or labs, this report reveals that some aspects of R&D had already been affected, but not all. From this research we know that budgets will be affected for the next few years and R&D activity may well be localised as people rethink supply chains. A lot is changing very quickly, and we do not want to make any presumptions or develop hypotheses without hard evidence. It will certainly be interesting to see how Covid-19 impacts R&D, but first the dust must settle.

There is cause for optimism; innovation is vital for steering us out of the crisis. Immediately, it has forced businesses to innovate quickly and find new ways of operating, mainly through technology, giving R&D departments newfound importance. We can already see that those adapting quickly will emerge triumphant.

Having said this, most questions are not Covid-19 specific so can be analysed independently of its influence. For example, technology is a major theme throughout. The growing complexity of the R&D role makes technology increasingly crucial for projects to be fruitful. Fortunately, there are new, advanced tools which bring these capabilities, but because lots of companies do not have these in-house, many are looking to private resources to achieve their goals by outsourcing or creating hybrid models for fostering innovation.

From a funding perspective, incentives are still vital, with R&D tax credits growing in popularity. Yet, there are new opportunities for those who are looking to secure fun- ding through independent means, with private influences – such as crowdfunding or equity debt – becoming more popular, largely to the benefit of SMEs who do not have the resources themselves. Again though, it’s likely that the public and private funding landscape will change radically in the coming years due to Covid-19. We anticipate this to become clearer in 2021, but we believe that generally governments will be aiming to ramp up R&D funding even more than before.

One area they may direct this funding is sustainability. Sustainable R&D will be pivotal to finding a way out of the climate crisis. As a globe, we need to make our economies more sustainable by designing new products and ways of operating. Section Three provides some detail on what businesses are doing at the moment and how sustainably motivated R&D can be scaled, with the need for definition being a key factor.

R&D is the commercialisation of ideas and it continues to be a fascinating field. We hope you find the following report insightful and that it provides guidance on how to make your R&D as productive as possible.

Section 1 – The Innovation Landscape

With the world in 2020 changing quicker than ever before, it is the role of R&D departments to respond to that change. Covid-19 adds to the list of external forces R&D departments are facing, but there are numerous underlying trends in how businesses are responding to change which would exist with or without Covid-19.

This section takes a deep dive into those trends, covering the attitudes, drivers, approaches, and preferred locations of business R&D activity, uncovering numerous parallels to last year’s research as well as several striking deviations. These trends will certainly be hindered or accelerated as the implications of Covid-19 become clearer and innovation strategies adjust. But, for now, this is how businesses are innovating.

Great expectations

When firms are asked if they are doing ‘enough’ R&D, attitudes are broadly the same as last year, with 86 per cent answering positively, up from 83 per cent. However, this positivity is not all it seems. Last year’s report pointed out that high levels of satisfaction could indicate complacency. Spending shows that businesses are generally not hitting R&D targets, revealing a disparity between government and business opinion. Mark Smith, Partner at Ayming UK, suggests, “It’s better if companies recognise they’re not doing enough because – chances are – they’re not. Governments must build recognition that more needs to be done.” In support of this, the least confident countries are the UK and Germany, which have notoriously innovative business cultures.

The two most confident countries are Belgium and Slovakia, both with 100 per cent positive responses. Stefaan Heyvaert, Innovation Performance Manager at Ayming BeNeLux, points out that this is about self-perception. “It comes down to whether a business thinks it could improve. Would these companies still hold this view if they knew the average spending of their peers was higher?”

Once again, there is a big variation between sectors. The R&D-intensive Healthcare/Pharmaceutical sector remains the least satisfied, at 78 per cent. Notably, 100 per cent of Energy/Biotech respondents are satisfied, up from 92 in the 2020 edition. This is surprising. Although companies in these sectors have shifted gear recently and ramped up R&D efforts to transition to sustainable models, there is still intense international pressure and they must invest heavily in R&D to stay relevant.

Of course, the responses to this question will be highly dependent on how R&D is defined, which varies between sectors, nationalities and job roles. For example, Jan Lucas, Managing Director at Ayming Germany, suggests, “Being Dutch, I notice that Germans tend to have a different, much more restricted perspective of innovation compared to other countries. Germans associate R&D much more with research than development, and therefore do not recognise part of their activities as R&D, where other countries do.” Germany introduced an R&D tax system at the beginning of 2020 based on the international R&D definitions, which will probably change their estimations about the amount of R&D they are carrying out.

Conflicting ideas of what R&D is becomes further apparent when looking at job roles, with 78 per cent of MDs satisfied compared to 95 per cent of R&D Mana- gers. This may indicate that MDs fail to see the nuanced nature of some R&D. Because innovation is becoming more complex, it is increasingly about incre- mental gains as opposed to radical innovation. Carlos Artal, Managing Director at Ayming Spain, states, “Today the goal is to take something and make it better. It’s all about constant small improvements. Business leaders need to be fully aware of exactly what constitutes R&D so they know how much they are doing.”

Nuno Tomás, Managing Director at Ayming Portugal, agrees, suggesting that there are challenges in measuring R&D activity accurately. “We have to measure what is being done in innovation, but also how successful it is.

Eventually we may see movements away from measuring by investment and more by output.”

Fundamentally, business leaders should rarely consider their activity to be enough, and to do so they must know exactly what constitutes R&D to gauge this. Governments must make sure that they provide clear frameworks, but it is the responsibility of the business to know when they need to ramp up activity.

Creating success

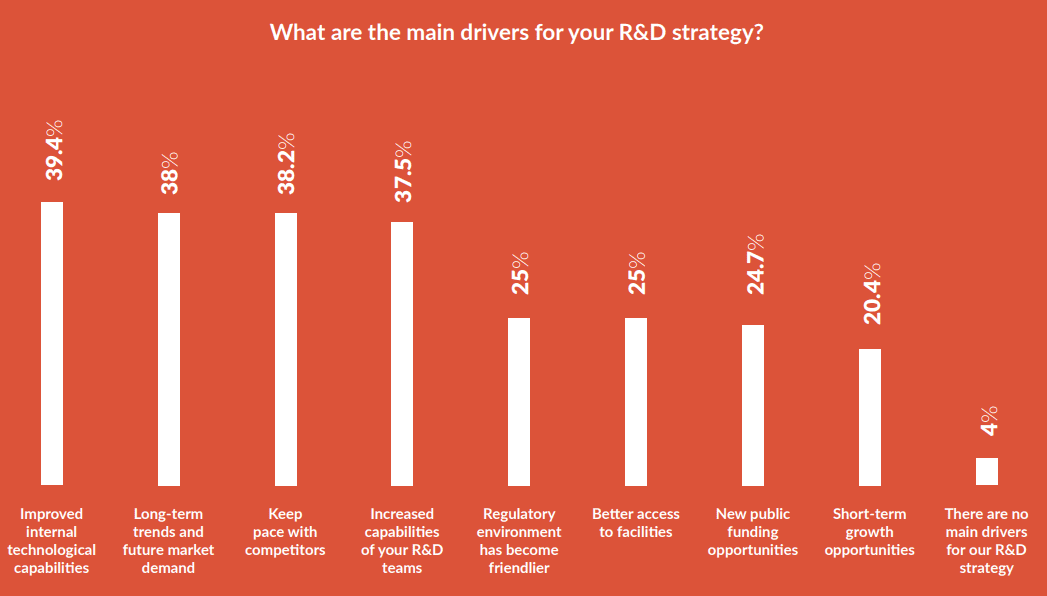

Strategies are predominantly driven by external influences of future demand and competitors, at 38 per cent each. Both are largely about survival. Businesses are aware they must understand where the market is heading and create products and services that fit. As Thomas Folsom, Managing Director at Ayming USA, points out, “It’s imperative you pick a direction. But if you make the wrong product, or develop the wrong service, and nobody wants it, you won’t be around very long.” Heyvaert adds, “Businesses must plan for different time horizons (short-, mid- and long-term). Even in these trying times, companies must not forget to keep investing in those long-term projects.

After all, those more ambitious projects are the ones that will bring untapped markets or market segments.”

People are actually starting to implement technology that has been talked about for a long time. Now the cost has come down, it’s taking off and you can basically tailor your computing resources to your needs, without having to maintain an overhead for infrastructure.’’

Mark Smith

Companies now have cheap and easy access to advanced tools that can be used to accelerate innovation and connect parts of the business in ways previously not possible. Smith points out, “Construction has been slower to innovate and only recently has begun making a transition by introducing technologies like 3D printers. However, firms can also gather data from the tools they use and learn from statistics to boost productivity. Technology is the glue that holds innovation together.”

The need for technology is also influencing innovation processes. Although internal R&D resource is most relied on, at 61 per cent, companies are less likely to rely on it exclusively. Things are getting extraordinarily complex and most innovation now requires complicated technology that companies do not have in-house. As such, they must look externally for additional capabilities. To solve these challenges, collaboration is an obvious option.

Not only can it increase chances of success, but it saves money. It’s common practice, particularly across the EU. In France, which is the most collaborative country, Fabien Mathieu, Managing Director at Ayming France, explains that, “Car makers at the national and EU level are pooling their engineering resources. As has been the case with motor development for the last 20 years, it is now a big bur- den to develop new technologies like autonomous driving, so they exchange a lot. Traditional tier one suppliers and young tech start-ups play a key role in that process. A whole ecosystem has emerged.”

Knowing this, you would expect colla- boration to be up, but it’s down from 51 to 43 per cent. Intellectual property concerns are of course at play here. “It’s a poker game when you work with a competitor. You don’t want to give too much away,” suggests Mathieu. This argument is bolstered by the finding that internal resource is so dominant for the fast-paced Manufacturing/ Consumer Goods sectors.

However, businesses underestimate what it takes to collaborate. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) says, “There can often be a mismatch. Parties do not think enough about differences in cultures, procedures and expectations, which can lead to disagreements. A lot of small companies look at big companies as a bank to support the risk-prone parts of their development, whilst big companies see smaller companies as external, risk-free investments on development of IP, which – if successful – can be acquired.”

Technology may also be contributing to a decline in collaboration. Folsom (USA) says, “There is certainly more technology available at the lower level, so firms don’t need the support of bigger tech companies. Why would you collaborate with Google or some big multinational who makes you sign an unfavourable contract?”

Rather than collaborating, innovation models are moving towards external private resources, with a significant rise from 35 to 48 per cent this year. These are companies that make a profit from the interaction, so this can be categorised as outsourcing.

Take the financial services industry, which has the highest use of external resources at 59 per cent. Many finan- cial firms have slow processes and their structures are not set up to be agile, so they often buy their innovation. Smith points out, “There are tons of Fintechs who do one specific thing very well. A bank could hire people and do it themselves, but why not just use a third party? It’s often cheaper, better and faster.”

What appears to be emerging is a hybrid model, whereby big companies facilitate projects by establishing an ecosystem. Elisa Di Paolo, Director of Finance & Innovation Performance at Ayming Ca- nada, explains the situation there: “Large companies have spin-off companies where a team of researchers start their own entity, allowing them to benefit from SME tax rates. However, this can backfire because the innovation is usually sold to a foreign company. Acquisitions are playing a big role here.”

Similarly, many large corporations have entrepreneur programmes with the intention of acquiring the successful innovations. In Spain, Artal looks at Mahou’s startup academy, “Mahou offers support for innovative startup ideas in exchange for a stake in the company. It works for both parties: Mahou is spen- ding very little money on exploring lots of ideas, and entrepreneurs are more likely to succeed.”

Not only is this cheaper, less risky and creates more diverse ideas, but it’s often a quicker route to outcome. Both innovating internally and collaborating can make the process longer. This trend of using external private resources is likely to continue to mature in the years to come.

Setting up shop

The competition to attract R&D activity continues. International companies must weigh up factors such as local talent, taxes and political atmosphere.

Folsom (US) says, “In the last four months, I’ve had 10 companies asking me about setting up abroad and what incentives are available. As companies expand, countries and cities compete for their activity. Just look at Amazon; they essentially put out a bid to the cities for their HQ2 to see who would pull together the best package.”

There are obvious benefits to having these R&D centres as it creates snowball innovation and draws in an ecosystem. Tomás says, “In the past we had a situation where the universities and businesses were more segregated. Now universities often interact with large companies, increasing the skills and knowledge of our research community.” As was the case last year, the most popular approach is a combination of local and international innovation. However, both ‘locally only’ and ‘locally and internationally’ have lost out to ‘internationally only’, which has risen from 2 to 10 per cent.

This rise in international activity is propped up by the Finance/Capital and Healthcare/Pharmaceutical sectors, which have both seen large jumps. Tomás explains, “There’s lots of consolidation in these sectors. Companies are getting bigger through acquisitions, meaning they are becoming more global and looking to internationalise R&D departments.”

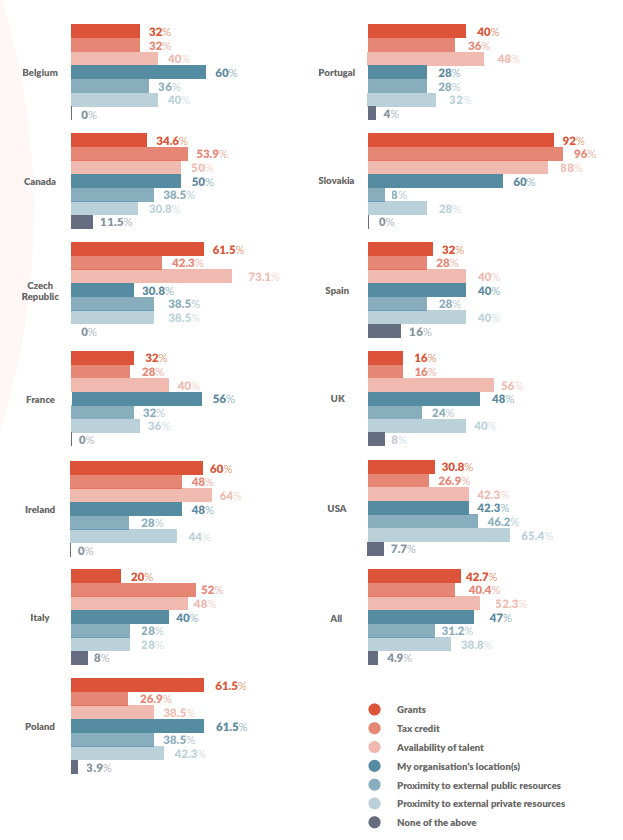

Which of the following influences where you decide to carry out your innovation?

France, Belgium and Poland are also very international, due to location and EU membership. Heyvaert highlights, “Belgium is central in Europe, has excellent higher education and is highly connected to our neighbours. It’s easy for our companies to do projects in the Netherlands or France.”

Germany remains the most common place for R&D activity. However, 20 per cent of German companies do their innovation internationally. Lucas explains this may soon change: “With the launch of our R&D tax credit this year, we’ve now got a very attractive, broad ecosystem for R&D with which the Government aims to increase the amount of innovation in local German companies as well.”

At 52 per cent, talent remains the biggest influence in determining location. However, external private resources have again taken a giant leap in influencing location decisions, with a rise from 24 to 39 per cent.

Conflicting with increasing use of tax incentives globally, these programmes are less influential on R&D locations, with a decrease from 45 to 40 per cent, with sizeable decreases in France, Spain, Poland and the UK. Fundamentally though, the decision is largely financial. Magdalena Burzynska, Managing Director of Ayming Poland, argues, “Moving activity abroad is about costs. Businesses are driven by their profit and, if they can maximise profits by moving abroad, they’ll do it. You can get some very talented deve- lopers in Eastern Europe for less than in North America or Western Europe. Pro-innovation countries that have more R&D incentives and reliefs effectively encourage companies to relocate.”

However, internationalisation faces obstacles. Not only is it often the same price for talent in Asia compared to Western Europe, but businesses favour having their innovation centres near their production and decision centres. Mathieu (France) argues, “When you delocalise your own R&D to another region, it causes fragmentation. You want to bring the marketing and sales closely together with your innovation department to align on objectives.” Smith adds, “I fully expect innovation to become more localised. People are often looking for more localised supply chains as a result of Covid-19.”

Ultimately, businesses are attracted to the best conditions and governments should strive to create an excellent ecosystem that combines a variety of resources to be in tune with what is needed.

Key observations

Overall, the landscape is becoming more complex – and that is before we even mention Covid-19.

contributing to a rise in larger businesses looking to create R&D centres abroad, creating competition for their activity. To be attractive, businesses and governments must work together to create the perfect ecosystem for fostering activity.

Looking ahead, businesses will have to adapt their strategies to the unfolding Covid-19 crisis, with digitalisation an immediate priority. However, the primary differentiator will be those who manage to allocate financial resources to innovate their way through the crisis.

Section 2 – Financing Innovation

Financial resources are extremely important for effective innovation. This section explores innovation finance and discovers that Covid-19 may level out innovation growth as budgets are cut.

Fortunately, there is cause for optimism. The funding landscape is maturing with new, sophisticated funding methods emerging, across both public and private spheres.

Current spending

We asked our respondents what percentage of revenue they were spending on R&D. Crucially, these answers were recorded in May, at the height of the Covid-19 crisis. At this stage, most R&D budgets were unchanged because activity had been signed off earlier in the year.

The picture is one of continued strong growth in R&D spending. Only 16 per cent of respondents report spending ‘less than one per cent’ of revenues, a fall from 25 per cent of respondents in last year’s survey. Conversely, there has been an increase in those spending ‘between one and three per cent’, from 31 to 42 per cent. These figures echo global growth in innovation spending figures. As Burzynska (Poland) points out, “Spending is ticking up across the EU. The market is getting more competitive and businesses now know it is more beneficial to innovate than engage in price competition.”

However, the answers will differ depending on what respondents define as R&D, an argument bolstered by Germany’s low figures, with a high proportion unsure of their budget at 28 per cent, despite Germany being a renowned R&D hub. Lucas (Germany) suggests, “It comes back to awareness about what is seen as R&D. If Germans knew more of the definitions commonly adopted in other markets, these stated budgets could easily be doubled without any change of activities.”

A lack of clarity can also be seen among business owners, as 29 per cent do not know if they have an R&D budget, compared to seven per cent of senior management. Smith (UK) comments, “It is tricky to know every single part of your business, but if they don’t even know if they have a budget, it indicates R&D is not a key pillar of their strategy.”

Sector results generally run parallel to last year’s. Finance/Capital has seen the most drastic change. Despite having the lowest spending last year, 20 per cent now budget ‘over three per cent’ of revenues. This trend is being driven by Fintech. Smith (UK) says, “Technology is now critical to financial firms. The CEO of JP Morgan recently said they don’t have an IT budget. If someone comes to him with a proposal that has a positive return on investment, they will spend the money.”

Healthcare/Pharmaceuticals remains one of the most R&D intensive sectors, with 21 per cent of companies allocating ‘more than three per cent’ of revenue to R&D. “For these companies, it’s not just about developing entirely new drugs, but improving production processes, such as new methods of chemical synthe- sis,” argues Burzynska (Poland).

Budgets in this sector are also kept ambiguous, with 19 per cent not knowing their budget and 17 per cent having no budget at all. These sectors are fast moving, and activity may need to go up or down depending on what changes throughout the year, whether it be new medical demand or new regulations. Terrazzani (Italy) says:

Cases of large companies which don’t know their R&D budget are usually pharmaceutical. These organisations are very complex, and R&D is spread across several countries. They will have their core plan for the year, but activity will deviate from it.”

Many countries have implemented incentives to boost R&D spending. The most popular option is R&D tax credits which, at 47 per cent, are closing the gap with self-funded – a positive development. As touched on last year, tax credits are a diverse and reliable form of funding. Compared to grants, tax credit applications are simpler

Covid-19 perfectly illustrates why pharmaceutical budgets are kept fluid.

However, the pharmaceutical sector is an outlier here. More widely, it is extremely important that firms allocate a budget for R&D. Activity needs to be carefully planned to hit an innovation target, so it is positive to see that 90 per cent have a defined budget. Folsom (US) agrees, “It shows people understand that you have to innovate, or you’ll be left behind. When preparing budgets, it’s definitely one of the key things to factor in or it won’t happen.”

Many countries have implemented incentives to boost R&D spending. The most popular option is R&D tax credits which, at 47 per cent, are closing the gap with self-funded – a positive development. As touched on last year, tax credits are a diverse and reliable form of funding. Compared to grants, tax credit applications are simpler and, crucially, the funding is volume-based and the activity is business-led as opposed to predetermined.

Kristina Sumichrastova, Managing Director at Ayming Czech Republic & Slovakia, agrees, “Tax credits are definitely growing in popularity. More businesses are learning of their benefits and becoming familiar with applications.” However, despite progress, processes need to be streamlined to ensure further adoption. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) says, “Until a few years ago, the Belgian federal government service still required technical documentation to be submitted via the postal service.”

Contradicting the growth of national innovation budgets, both international and national grants are down on last year. Although awareness plays a role here, the long applications for grants are discouraging.

For example, the big gaps in popularity between tax credits and grants in Italy and Belgium can be attributed to complex processes. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) explains, “In Belgium, you have three different regions and two different languages. And while the main parts of an application are similar for the three regions, there are subtle but critical differences in the requirements as dictated by each.” But this is the case in many countries, where grants are split between international, federal, and regional grants. These are still an essential part of the funding puzzle, particularly for Eastern European countries, which are highly dependent on international grants, so more transparency is needed to encourage further involvement.

Not only can application processes be complex, but they require a detailed understanding of the product and the sector. In the case of R&D tax credit applications, they require technical knowledge. Tomás (Portugal) says, “You need a deep understanding of the business to provide the necessary detail.”

Essentially, people need guidance, particularly as projects become more technical. As a result, companies are using consulting services to unlock incentives, whereas the use of accountants has gone down considerably, from 38 to 25 per cent.

Mathieu (France) suggests, “In France, firms must have a written description of R&D projects to justify their eligibility to the scheme and the valuation when they declare to the tax authority. This requires, first and foremost, a deep scientific expertise, which is both exhaustive and accurate. Accountants simply don’t have that. When a tax audit is triggered, firms that have the right scientific expertise at their side to defend their position are better placed to succeed, and I believe this trend will continue to develop as R&D complexity increases.” This is supported by the findings, with the more scientific sectors, such as Energy/Biotech, using R&D specialists most at 50 percent.

Yet, if incentives are not an option and a business cannot fund its own innova- tion, it must look externally. This is often the case for SMEs, which do not have the capital or the resources for applications. Private funding, therefore, plays a vital role for SMEs.

Positively, Equity/Debt funding is becoming increasingly common, up from 28 to 34 per cent. Investors are looking for opportunities where they can make a substantial return with innovative companies. Folsom (US) suggests that this rise is due to the concentration of wealth, especially in the US. “We now have quite a few clients who have independent funding,” he says. “There are a lot of wealthy people who are sceptical of the stock market. Their money can go further elsewhere, so they are making investments in small, innovative companies.

The downside here is that it is not a level playing field internationally. Artal (Spain) points out, “There’s no way you can compare the Spanish venture capital or investment fund industry to the US or UK. Companies there have more funding options.”

The Big Four are aware of the opportunity in R&D consulting and our data shows an increase in the uptake of their services from five to 15 per cent of respondents. However, more technical knowledge is often needed to optimise applications and the use of specialist consultancies has risen from 29 to 34 per cent. Terrazzani (Italy) concludes, “For me, it’s a natural evolution to move to specialists over generalists. Specialists can talk to the client using the same language because they usually come from the same STEM backgrounds.”

Although it is positive to see the growing uptake of incentives, these should primarily be used to supplement activity as opposed to fund an entire R&D strategy. More established businesses can usually fund innovation themselves due to their deeper pockets and clearer direction. The Automotive/Industrial sectors are a visible example of this, with 55 per cent of respondents funding their own R&D. Smith (UK) argues, “R&D in automotive has been critical since the 1980s when Japanese manufacturers started overtaking American and European manufacturers in leaps and bounds. It’s built into budgets for them.”

Folsom’s notion that people are wary about stock investments also helps to explain the drastic rise in crowdfunding, which has jumped from 13 to 30 per cent. This is a new funding mechanism that still has big potential for growth.

Crowdfunding is not as commonly used, but provides an easy and inexpensive way to collect resources compared to the processes of grants and taxes.”

Mathieu (France) highlights technology’s role in this, “It’s a digital way of accessing a wider range of participants. You can post your idea and receive investments ranging from $10 to $10,000, a concept unheard of not that long ago”

However, crowdfunding is not always applicable and is specifically tailored to SMEs. For example, it may work for Fintechs, which account for the rise from 14 to 36 per cent in Finance/Capital, but for Energy/Biotech companies it is clearly less useful, with only 16 per cent using it as a funding mechanism.

Burzynska (Poland) explains how company size is important here, “In Poland crowdfunding is mainly used for smaller and media-promoted projects. If a company builds a new power plant, they need billions in funding, so crowdfunding is simply not an option.”

Overall, governments recognise the funding challenges for SMEs and we are now seeing new frameworks emerging that pair public and private investment, such as the EU’s EIC accelerator, which is a combination of a grant and private equity. Initiatives like this split the risk but also help make public funding for SME innovation more efficient.

Since Covid-19 emerged, many companies have slashed future budgets as they focus on short-term cash flow and maintaining liquidity. Terrazzani (Italy) suggests:

Covid-19 will affect R&D investment well into 2021, if not beyond. Businesses may have a vision, but now they need to have money to pay salaries and suppliers.

The financial effects have the potential to be long-term. Artal (Spain) says, “There’s a lot of pessimism in Spain. Everybody thinks there’s going to be a really big economic crisis.” A V-shaped recovery now looks unlikely, so governments need to find a way to stimulate their economies and find a route out of the Covid-19 crisis; for which innovation will be vital.

Naturally, immediate efforts stimulated innovation in key areas, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and vaccine research. However, most sectors have experienced significant drops in confidence, and the biggest drops have been in Chemical/Civil Engineering and Energy/Biotech. “These sectors are highly dependent on on-site work, presenting challenges under lockdowns,” suggests Burzynska (Poland).

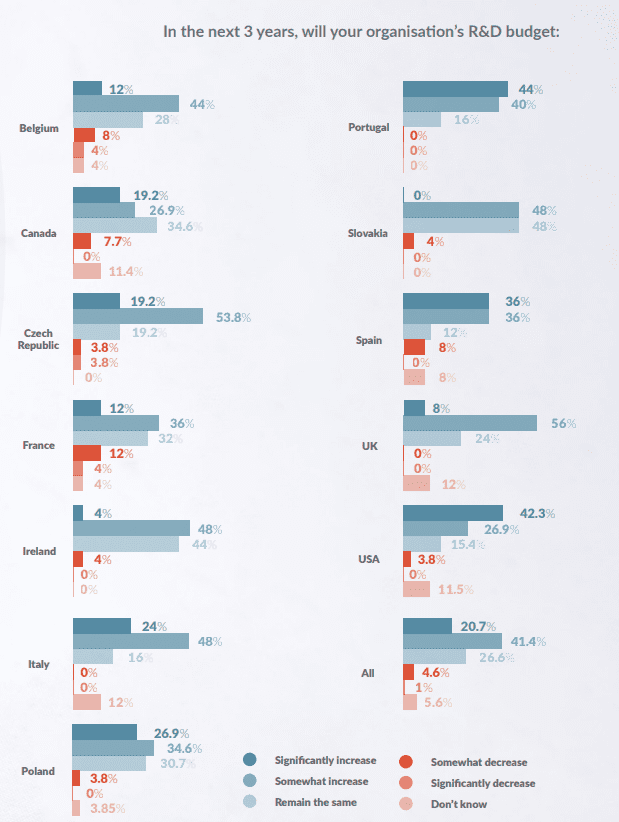

It may be a downturn on last year, but the majority are still expecting budget increases, which is surprising. Di Paolo (Canada) contemplates, “There was a lot of money going into innovation, so people may still feel optimistic.” However, public funding initiatives can take some credit here. Governments recognize how vital innovating is in this crisis, and, while businesses may reduce budgets, state funding is ramping up.

Supporting this, respondents remain positive about access to funding, which has even risen slightly from 53 to 55 per cent – against the odds. In Portugal specifically, the Government has made visible efforts to boost R&D confidence and has renewed its scheme to 2025. Tomás (Portugal) explains, “It’s important to have these signs of support to generate trust in innovation schemes.” Artal (Spain) adds:

People are also expecting a lot of economic relief from the EU, and we expect a significant portion of it to be allocated to R&D.”

Similarly, governments have also boosted grant funding, which Smith (UK) argues “will be crucial for those facing slashed budgets.” Therefore, it is now even more crucial for governments to streamline applications.

Covid-19 is also permeating into politics, with 28 per cent of respondents seeing political risk having a negative impact, up from 18, with those in Slovakia, Ireland, Spain and the Czech Republic particularly worried. Sumichrastova (Czech Republic and Slovakia) says, “We are likely to face a political backlash. Not only will policies change, but economic shocks always give rise to sentiments like protectionism.”

This is a large risk for Manufacturing/Consumer goods com- panies, whose global supply chains make them dependent on interconnected markets – hence political risk is seen most negatively in these sectors at 37 per cent.

Having said this, protectionism was already emerging. The trade dispute between the US and China has been destined to escalate and fracture global markets. Considering these trade tensions, the US is surprisingly relaxed about politics, which Folsom (US) blames on the timing of the survey, “A lot has happened since. The trade spat has gotten worse, there’s been civil unrest, and the handling of Covid-19 has turned the polls against Trump, who businesses generally favour due to the tax breaks.”

Growing international competition is also affecting talent.

Bigger markets have a constant demand for talent, which is supported by Germany and UK being the least optimistic.

Fundamentally, you cannot do R&D until you hire a team with the skills. This is becoming harder as R&D becomes in- creasingly sophisticated, as demonstrated by Chemical/Civil Engineering having the most negative outlook on talent, at 27 per cent. “This sector requires more specialised talents than other sectors.

In order to conduct R&D activity, businesses need large innovation teams, but unfortunately not enough talented specialists are available,” says Burzynska (Poland). This is creating problems for some markets. Tomás (Portugal) adds, “Our homegrown talent often moves abroad. We need to invest in universities to train people in STEM subjects.”

A solution may lie in technology. Not only has it enabled the continuation of the economy through digitalisation but, as touched on earlier, technology can facilitate R&D. Terrazzani (Italy) says, “People are more willing to invest in equipment that can be used to deliver positive change, such as data analytics.”

Therefore, there is a growing recognition that integrating technology into R&D can generate a positive return on investment – a notion highlighted by Automotive/Industrial, which has been proactive in using technology to boost productivity, and putting the most emphasis on the former.

Although a useful tool, technology is not quite replacing talent yet; software still needs programming. Folsom (US) suggests:

We need technology to make R&D more effective. Eventually, R&D may become automated but, for now, you still need a brain.”

Key observations

Despite strong pre-Covid-19 growth, budget reductions seem imminent.

The pressure is on to keep innovation flowing through the market downturn and, while funding may be evolving, incentives need to be simplified.

Any situation where businesses are not applying for funding where they can is a lost opportunity.

Section 3 – Sustainable Innovation

Economic growth has often been achieved at the expense of the environment. Profit is often put before planet – but the two can co-exist. Demand is high for solutions to the climate crisis, and business innovation is desperately needed to transform the global economy into a circular one and avoid climate catastrophe.

Rising to the challenge

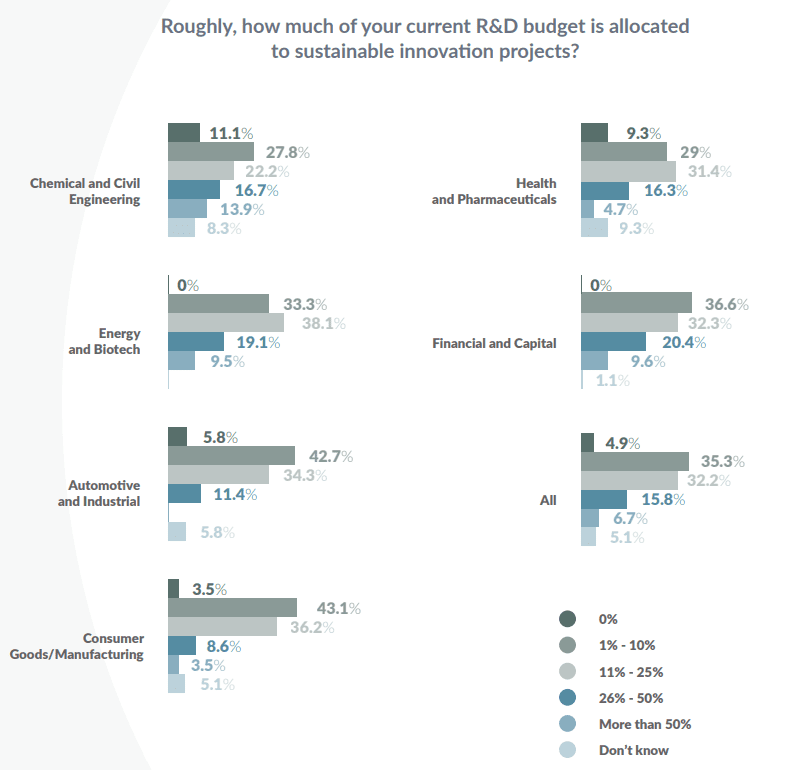

Most companies vocalise their support for sustainability, but it is not an R&D focus for the great majority. When asked how much of their budget is allocated to sustainable innovation projects, 35 per cent of companies spend ‘between

1-10%’, and only seven per cent of companies allocate ‘more than 50%’ of their budget to sustainable projects, so it appears a few companies are leading the charge. Artal (Spain) states, “50 per cent is a lot, but it is something those in the lower brackets should be striving for. At present, most of this will be being driven by a few large companies.”

Tomás (Portugal), which has the highest portion of businesses spending ‘more than 50%’, says, “I’m pleased to see such positive figures in Portugal. It’s not easy to say what the right amount is, but it’s fair to say that more needs to be done, and faster. The consumer demand is there so there is value in investing in sustainability.”

Naturally, the amount of investment will depend on the sector. Chemical/Civil Engineering has a big spread between the companies, with 17 per cent spen- ding ‘between 26-50%’ and 14 per cent allocating ‘more than 50%’. Di Paolo (Canada) suggests, “Some companies in this sector need to make products less toxic. Cleaning products for example increasingly have to invent alternatives if there is any chemical danger to the environment or customers.”

Despite a growing trend towards electric and hybrid vehicles, Automotive/ Industrial spends the least on sustainable innovation, whereas Finance/Capital spends a much larger amount, with a fifth of companies allocating ‘between

26-50%’. This brings into question definitions as there is a wide spectrum when it comes to what can be considered as sustainable R&D. Some projects will simply minimise a business’ carbon footprint, whereas some will be radically transforming how industries operate. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) states, “It’s easy for a company to say it spent 25 per cent on a project that only slightly reduces its carbon footprint. There is no distinction between simple improvements, such as finding ways to recycle better, and game-changing innovations.”

Folsom (USA) adds, “Just because a project isn’t labelled a sustainability project, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have an element of sustainability. It may simply not comply with certain specifications. There’s a lot of definitions out there so it would be good to see more uniformity and international consensus on defi- nitions.” Evidently, there needs to be a realignment of how businesses report their sustainable innovation efforts. “Once categorisation becomes clearer, businesses will be able to make a judgement about increasing their sustainably motivated R&D, which will likely drive these figures up,” Smith concludes.

Scaling sustainable innovation

To find out how sustainable innovation might increase, we asked our respon- dents where the pressure comes for these to undertake sustainable innovation projects. Generally, the results are relatively even, but competitors was the least

important factor at 34 per cent. This is expected; as Folsom (USA) highlights, “Competitors are less important when it comes to environmentalism because you have a specific goal in mind outside of just profit.”

Automotive/Industrial is an anomaly here and is clearly being driven by competition, with 60 per cent of respondents naming this as their key pressure. Smith (UK) adds, “Not only have lots of countries legislated to ban petrol and diesel cars, but the race is on for electric vehicles. Tesla’s a huge disrupter and has overtaken long-term market leaders in its value despite producing a fraction of the number of cars.”

Considering the rhetoric coming from people across the globe, one would expect customer demand and legislation to be more prominent concerns, both being fairly low at 36 and 35 per cent respectively. On consumers, Artal (Spain) explains, “Sustainability is now something that the citizens are aware of and want. It’s no longer a ‘nice to have’. Younger generations are prioritising environmentalism and businesses must rise to this demand or they will be gone in 10 years.”

However, the most popular driver was that sustainability will improve business performance, at 43 per cent. Di Paolo (Canada), “It means that companies are doing it for their own productivity. It’s grown organically because it makes good business sense.” Smith (UK) links this to the fact that many projects’ main aim might not be to become sustainable, but it is a secondary benefit to boosting efficiency. For example, he argues, “if you reduce your energy consumption, which is always a high cost, you are actually just improving how your business runs, but it also has a sustainable outcome.”

Whilst it is positive that sustainable projects produce long-term benefits and tangible business results, this presents problems because businesses are chiefly motivated by profit and will avoid radical change if they can. As established in Section One, innovation is increasingly incremental and big businesses will aim to improve existing processes as opposed to devising something completely new. Lucas (Germany) supports this, saying:

In a big factory, you could have machinery worth 100 or 200 million euros. This has to be amortised. Take the car industry: unfortunately, it’s far easier and cheaper to improve the software for diesel engines, than to look more seriously at electromobility.”

The survival of our environment now requires a radical transition to sustainability, so the pressure on businesses needs to be ramped up.

How, if at all, have the following factors positively or negatively affected your business ability to undergo sustainable innovation?

Additionally, to pinpoint what the obstacles are, we asked how certain fac- tors have affected business’ capability to undergo sustainable innovation. Our respondents viewed most factors positively, with 70 per cent of respondents ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ positive about talent, and 69 per cent positive about lea- dership. Once again, though, technology stands out, with 76 per cent ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ positive about existing technology.

Similarly, from a forward-thinking perspective, when asked what will help a business to successfully innovate, better technology is significantly ahead of other factors, at 38 per cent. As established in Section One, technology is helping businesses with day to day tasks and advances in analytics and other Industry 4.0 elements are facilitating R&D.

Conversely, Covid-19 is predictably reported as having a negative effect, with ‘very negatively’ and ‘somewhat negatively’ at 22 and 26 per cent respectively. Smith (UK) retains an optimistic outlook, “Indeed, sustainable innovation may take a back seat if it is not core strategy, but there is a real opportunity in the long term. The reduction in air pollution in cities like London has brought the environment front of mind for many. And soon there’s going to be a lot of Government funding coming in that may well be directed towards a green

Leadership through policy

The research uncovers a recurring the- me whereby government intervention is seen less favourably when it comes to stimulating sustainable R&D. There are two primary ways a government can steer economies in a sustainable direction: regulation and incentives.

The research uncovers a recurring theme whereby government intervention is seen less favourably when it comes to stimulating sustainable R&D. There are two primary ways a government can steer economies in a sustainable direction: regulation and incentives.

When asked where the pressure comes from to undergo sustainable innovation, legislation was the second least important, which is slightly surprising. Smith (UK) contests, “It can have a huge impact. When China legislates for something, they have thousands of companies innovating to try and fill that niche.”

Additionally, when asked how certain factors have affected sustainable innovation, incentives and regulation are viewed with relative impartiality compared to other factors. In the case of regulation, ‘somewhat negatively’ is higher than average at 11 per cent as is ‘neither negatively nor positively,’ at 26 per cent, indicating many companies see it as an irrelevance.

Di Paolo (Canada) says, “These are curious findings. There are often initiatives to reach the goal that the country wants. For example, we will not have plastics when grocery shopping anymore. You have to use either a paper bag or bring your own bag.” An example which helps to explain why Consumer Goods/Manufacturing firms are by far the most positive about regulation, at 67 per cent positive.

On the other hand, the Automotive/Industrial sector is least positive about regulation, with 23 per cent saying it has had a negative effect, which is counterintuitive bearing in mind that many countries have made new regulations that phase out petrol and diesel cars, most within the next twenty years. Artal (Spain) voices his surprise at the findings, “There’s been a huge upheaval with petrol cars. Nissan recently had to close a plant in Barcelona because they were not able to manufacture any electric vehicles. Suddenly all manufacturers were looking for an alternative. I would say regulation is driving lots of Spanish sustainability.

From a forward-thinking perspective, we also asked our respondents about what would help them to do more sustainable R&D. Once again, government intervention emerges distinctly unfavorably, with government guidance being the lowest at 16 percent, followed closely by increased regulation at 17 percent. This is intriguing, considering that history has shown us that regulation is often necessary. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) argues, “The moment you take away regulations, do the large companies behave as well as before? Rarely. They’re driven by profit, and sustainability is expensive, so it is highly unlikely that you will see the desired transformation without it.”

Of course, impressions of government intervention vary greatly between countries. Germany is the only country that calls for more regulation in the future. Lucas (Germany) argues, “It’s a cultural thing. Germans like everything to be regulated so that they can have a clear process. From the German perspective, they would rather have a framework in place to help them nail the innovation.”

The USA is also very positive about the impact government intervention has had, with 50 percent answering ‘very positively,’ whereas Spain and Belgium are less enthusiastic, with ‘somewhat negatively’ at 28 and 24 percent, respectively. This may be because the USA has had less regulation compared to Spain and Belgium. Heyvaert (BeNeLux) suggests, “Environmental regulations are necessary but are a component of economic regulation, which sometimes negatively impacts competitiveness and innovation. Sustainable regulations must be designed to foster competition and boost performance.” As such, although there is a lot of emerging regulation that focuses on emissions and decarbonization, it can impede innovation if not well-executed.

Mathieu (France) argues, “Regulation can overshadow the goal. There are cases where the R&D aim is just to be compliant with regulation, rather than achieving sustainability. The focus needs to be on what the environmental needs are, rather than compliance, so instead of making rules, they should incentivize.”

This brings us to the other key method of government intervention: incentives. Although still viewed positively, existing schemes are one of the least popular factors affecting sustainable innovation, with 26 percent saying ‘neither negatively nor positively.’ Consequently, it should be a priority to upgrade sustainable incentives.

Supporting this, it is extremely significant that, when we asked what would help businesses improve sustainable innovation, ‘increased tax incentives for sustainable projects’ came in a comfortable second place behind technology, at 28 percent. This is a clear call for more targeted government programs to act as universal drivers for sustainable business solutions.

The targeted nature of grants makes them an obvious option, but for the reasons mentioned in Section Two, they have their drawbacks. Ideally, firms should strive to strike a healthy balance of both grants and tax credits. All available funding should be accessed where possible, but creating additional sustainably targeted R&D tax credits could provide the required boost. “A supercharged R&D tax credit which provides more credit on costs for environmental R&D projects could be a very powerful tool,” says Heyvaert (BeNeLux).

For this to work, it would require clear definitions. If countries effectively categorized sustainable R&D projects and rewarded businesses accordingly through supercharged tax credits, it could be transformative. At present, the schemes outside of targeted grants fail to distinguish and incentivize.

Mathieu (France) predicts that sustainable R&D will become much more distinctive, and eventually, all R&D activity may have to have sustainable aims. He says, “I would say in the future innovation will only be accepted if it is recognized that it has a positive impact. All projects will have sustainability at their core. That’s where I think we are heading.”

Key takeaways

The lack of uniformed definitions makes it difficult to know exactly how much business are spending on sustainable R&D. Either way, it is probably not enough at this stage of the climate crisis.

At present, sustainable innovation is mostly being grown organically, with businesses mainly doing it because it improves their productivity. To really give sustainable R&D a boost, governments should develop criteria to launch supercharged tax credits that can be applied to all sustainable R&D activity.

Summary

This year’s story is one of increasing complexity. Innovation has been heading in the right direction, but Covid-19 represents a real pivot point – one that could see budgets reduced, but could just as easily provide a catalyst for innovation.

In any case, to drive innovation forward there needs to be greater leadership, particularly from governments, when it comes to providing funding opportunities and promoting the common understanding of R&D required to better measure outputs and facilitate improved collaboration.

The landscape

The innovation landscape is becoming more complex, even before Covid-19 is factored in. The process is becoming more technical and businesses are finding it difficult to innovate without support. Businesses and governments must work together to create an effective ecosystem for fostering R&D activity.

- Avoiding Complacency: Eighty-six percent of respondents believe their firm is doing ‘enough’ R&D, up from 83 percent last year. However, this increase should not automatically be taken as a positive, as it could indicate complacency. Governments need to build recognition that more work remains to be done in this area.

- Collaboration – Desirable but Difficult: Collaboration remains an important enabler of successful R&D, as it increases the chance of success and reduces costs. However, the number of firms collaborating has decreased from 51 percent last year to 43 percent. Different cultures, procedures, and expectations are making successful collaboration more difficult.

- Governments Need to Define R&D: R&D is defined differently across sectors, nationalities, and job roles. Businesses need to ensure they clearly understand what constitutes R&D so that they can accurately measure their R&D activity.

- R&D for the Long-Term: The drivers of R&D among respondents are varied, but strategies are largely motivated by long-term considerations. Future demand and competitors are two of the most popular drivers, with each being selected by 38 percent of respondents.

- Technology is King: Technology is the most popular driver of innovation, cited by 39 percent of respondents. This shows how advances in technology are facilitating R&D projects and creating a snowball effect in innovation.

- Outsourcing Models: Rather than collaborating, innovation processes are increasingly dependent on external private resources, with this approach rising from 35 percent to 48 percent this year. Businesses are adopting a hybrid approach, where big companies establish an ecosystem that leverages these external resources.

- International Innovation is on the Rise: There has been an increase in companies choosing to innovate internationally only, driven by the pharmaceutical and financial sectors. However, it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, as the Covid-19 pandemic may cause businesses to localize more operations.

Financing Innovation

Despite budgets increasing over the past year, reductions seem imminent as the impact of Covid-19 is felt. There must be a continued push to innovate in the face of a market downturn, with state incentives playing a key role.

- R&D Spending on the Rise Pre-Covid-19: There has been strong growth in R&D spending, with those allocating between 1-3 percent of their budgets to R&D rising from 31 percent last year to 42 percent.

- Funding Varies by Size: Incentives are used as supplementary funding. Larger firms are typically able to fund the bulk of their R&D on their own, but SMEs require external funding.

- State Incentives – Important but Complex: Many countries have implemented incentives to boost R&D spending, with the most popular option among companies being tax credits, used by 47 percent of respondents. However, the complex nature of these incentives may limit their broader adoption.

- Expert Help Required: Due to the complexity of these incentives, there is an increasing reliance on specialist R&D consultants as opposed to accountants when companies need external support.

- Jump in Private Funding: More businesses are turning to private financing options like crowdfunding and equity/debt funding, as investors recognize the benefits of investing in small, innovative companies.

- An Uncertain Future: The impact of Covid-19, whether financial or political, has reduced optimism for the future, with expectations for budget increases, big or small, down by 12 percent compared to last year.

Sustainable Innovation

Currently, sustainable innovation is being driven organically, with companies seeking to improve their own productivity. Greater government initiative is needed to drive sustainable innovation forward with more urgency.

- Important but Not Vital: While most companies vocalize their support for sustainability, it is not a primary focus in R&D for many. Only 35 percent of companies spend between 1 percent and 10 percent of their budget on sustainable innovation projects.

- Impact of Covid-19: Unsurprisingly, Covid-19 has had a negative effect on businesses’ ability to pursue sustainable innovation. This is largely because sustainable innovation is often seen as a luxury rather than a necessity.

- Sustainable Innovation Driven Organically, Not by Governments: When asked what drives them to develop sustainable R&D, companies indicated they were more motivated by business performance and their company’s values rather than by government legislation.

- Future Growth Driven by Greater Definition: Government intervention alone is not the solution to increasing sustainable R&D. However, governments must push for clearer definitions of sustainable R&D and develop targeted, supercharged tax incentives to encourage further growth in this area.

Methodology

Ayming’s second International Innovation Barometer provides comprehensive yet accessible insights into the biggest challenges and opportunities for business innovation around the world. The report offers an enhanced understanding of the current international landscape for innovation, as well as an analysis of innovation financing and views on the topical issue of sustainable innovation.

To complete the Barometer, Ayming conducted a survey of 330 senior R&D professionals, CFOs, C-suite executives, and business owners across 13 countries:

The data was gathered in May 2020, and as such, some of the effects of the global Covid-19 pandemic are reflected in the responses.

Senior members of the Ayming global innovation team have thoroughly analyzed the resulting data and contributed their analysis to the findings, all of which is detailed in this report.

Note: All total percentages in Sections One and Two exclude Germany to allow for comparisons with last year’s findings. Totals in Section Three include Germany.

The Ayming Institute is the think tank of the Ayming Group.

It brings together all the value-added knowledge produced by experts to think about tomorrow’s business performance.

Profit and Planet

The third book of the Ayming Institute advocates for technological change to make our businesses and industries more sustainable and more respectful of our environment. Investing in sustainable development is the only viable long-term strategy for companies to preserve their profitability and continue to grow.

The issue of sustainable development has been at the heart of our concerns for many years. We have been a signatory of the United Nations Global Compact since 2010. We consider the social and environmental issues of our clients in our offerings, across our various areas of expertise: Operation, Innovation, and HR.