Shelter and Innovation

Innovation has been the beating heart of the built environment since early humans first made shelter. From these humble beginnings, through trial, error, and ingenuity, humanity has constructed a world of wood, steel and concrete which dominates the landscape.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly when our first foray into man-made shelter took place, the archaeological footprint is slim at best, but combined with anthropological studies we know that they were probably built using a combination of stones and tree branches, such as the one discovered on a hillside at Chichibu, north of Tokyo, Japan.

In other areas of the world, the discovery of incorporating mud into wooden structures would have been a massive improvement to the occupants’ lives, sheltering them from the wind and rain, and providing warmth in the cold nights. Over time developed into shaping mud into blocks and drying them in the sun to create a strong brick, allowing Egyptians in 3100BC to start building flat-topped houses out of clay bricks and wood.

600 years after this, Assyrians discovered that if they baked the bricks in an oven or kiln it made them even stronger. Glazed bricks were also invented, making them more durable and water proof. Innovation begat innovation.

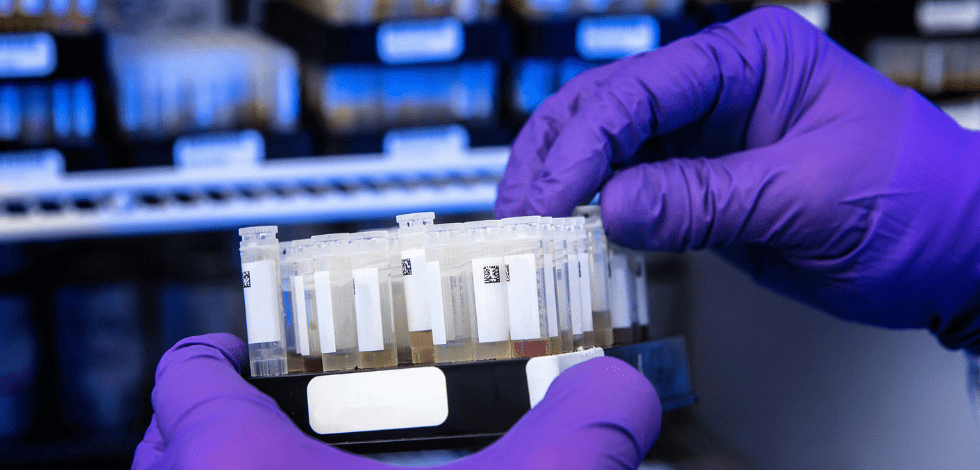

An example of a rural brick making kiln in India | Source: By McKay Savage [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://www.flickr.com/photos/mckaysavage/4040024973/in/photostream/)], from Flickr

A Brief History of Concrete

It is difficult to attribute the discovery of concrete to any one person, or any one civilisation for that matter, and that is due to the definition of concrete and the archaeological record.

Concrete-like material has been discovered as early as c.6500BC, by Bedouins of southern Syria and northern Jordan, who used it as a mortar for rubble-wall houses, concrete floors and water-proof cisterns.

It was also used by the Egyptians in the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza, c.2500BC, again as form of mortar for the casing stones that cladded the famous pyramid.

By 600BC the Greeks had also discovered a form of concrete. However, it was Rome, whose development of cement into a truly monumental building material shaped the built environment in concrete.

Opus Caementicum

Roman concrete was used throughout their empire, in building projects of all shapes and sizes, from aqueducts and temples, to bridges and triumphal arches. Many of which still stand strong to this day – a huge testament to the Romans’ engineering ability. The widespread use of concrete by the Romans led to the Roman Architectural Revolution, also known as the Roman Concrete Revolution.

A classic example of the innovative use of Roman concrete is the Pantheon, a temple dedicated to all Roman gods. The first iteration was commissioned by Emperor Augustus’ right-hand man, Marcus Agrippa, but was burnt to the ground. The present building was completed by Emperor Hadrian, of Hadrian’s Wall fame, and is now an operating Catholic church. For over 1300 years the Pantheon in Rome held the record for largest dome in the world, and to this day is the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

The Pantheon, Rome | Commissioned by Emperor Hadrian, the Pantheon has the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

Roman concrete, opus caementicum, was essentially made of two basic components:

- Aggregate

- A mixture of rubble, using anything from rock, ceramic tiles, and even the remains of demolished buildings.

- Hydraulic mortar

- Simply a binder, or cement, that is mixed with water and gets harder over time. These included gypsum and quicklime.

Roman concrete in this sense is not particularly different to modern Portland concrete, and similar to today they would cover it with brickwork or marble to make it aesthetically pleasing. However, the difference lies in their use of volcanic ash, which allowed them to create a concrete that could set under water, and actually grow stronger as time passed.

The Secret Ingredient

Pozzolana, or volcanic ash, is abundant along the Italian peninsula, and allowed the Romans to create an incredibly hard-setting concrete that was not only resistant to salt-water, but actually grew stronger when set underwater. This enabled the construction of elaborate baths, piers and harbours, helping them to become masters of the Mediterranean.

In fact, Roman marine concrete has been hailed as “the most durable building material in human history”.

According to researchers, published in American Mineralogist, it contains a rare material called aluminium tobermorite. Unlike modern Portland cement concretes, which deteriorate in a couple of decades under water, when Roman marine concrete is exposed to sea water, the tobermorite crystallises in the lime, reinforcing the concrete and preventing cracks from developing. And over time the crystals continue to develop, strengthening the concrete, akin to modern smart concretes…

Back to the Future

Concrete could quite easily be described as a catalyst for innovation, and more and more present-day companies are investing in its development. For example 3D printed houses, or even self-healing concrete. Surprisingly, there is huge potential for Roman concrete in a modern setting, and many scientists are dedicating their work to recreating this innovative material.

Currently, the process of making cement has a huge effect on the environment, and it’s estimated that it is responsible for 5% of global emissions of CO2. Italian company, Italcementi, recently developed an emission absorbing concrete which was used in the construction of The Dio Padre Misericordioso, named dramatically by the press as The Smog Eating Church of Rome. However, it’s unsure whether this innovation is as cost effective as its ancient cousin.

Rediscovering the exact mixture of Roman concrete, with its much lower cooking temperature and a far longer lifespan, could prove to be instrumental in future developments of the material.

No Comments