In July, the UK Government announced plans to follow in France’s footsteps and ban the sale of all petrol and diesel cars by 2040, with them being off the roads altogether by 2050 in a bid to encourage people to go electric. The Environment Secretary, Michael Gove, has warned of the dangers to the environment and people’s health if Britain continues to use petrol and diesel cars and that “there is no alternative to embracing new technology”. Embracing and enhancing new technology will lead to multiple sectors investing heavily in research and development in the coming years as companies look to meet public demand and expectation.

Latest stats published in August 2017 indicated there were currently 108,000 electric vehicles registered in the UK, with 22,000 registered in the first six months of 2017. This represented 1.5% of the new car market in the UK, a long way off the global leader Norway’s 40.2% in 2016. The lack of uptake of electric vehicles in the UK can be put down to three primary criticisms: battery life, charging time and driving range.

Electric cars were originally prevalent in the late 1800’s, so much so that in 1900 one third of the cars in New York, Chicago and Boston were electric. However, developers including Thomas Edison ran into the same limitations and criticisms facing car manufacturers today of power supply and distance. Once the Model T was introduced by Henry Ford in 1907, there was already greater demand for long range vehicles due to the improvement of American roads, which had a natural adverse effect on demand for electric vehicles. Over the last 20 years, electric vehicles have gradually increased in the public eye, from the Toyota RAV 4 in 1997 to famously the Tesla Roadster in 2008. However this will have to change given the recent announcement.

There are currently around 40 electric vehicle models available in the UK, ranging from the high end Tesla Model S, from £56k with a 381m range and 9 hours charge time, to the popular Nissan Leaf, from £26k with a 124m range and 12-15 hour charge time. Both the price and charge time will need to be improved which will require development to do so.

The announcement of the 2040 deadline raised a lot of questions on how various sectors will need to respond in order to meet public demand and the impact of phasing out cars which use internal combustion engines.

Car manufacturers need to act now to stay ahead of the competition

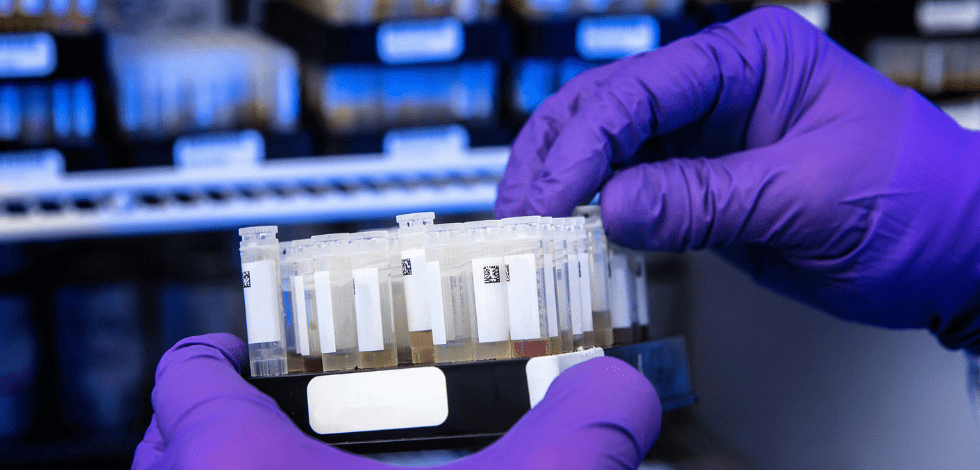

As car manufacturers are being forced to change how they develop and manufacture their vehicles, similar to the drinks industry reacting to the Sugar Tax in 2015, they will have to increase their already substantial R&D activities to improve on the current state of knowledge of electric batteries. Although they have 23 years until this is enforced, car manufacturers should be looking to invest heavily in their R&D activities in the coming years to improve the performance of their electric batteries and ensuring they are ahead of competitors. Whilst most car manufacturers already have an electric vehicle in their fleet of cars, these are not without their limitations, not only within the battery itself but also how they are powered.

As of 1 August this year, there were 13,159 connectors across 4,587 locations. With the charging time ranging from 30 min to 15 hours, depending on the kWh, this is one of the key areas of development, not only in the charging time but also in the number of charges needed per journey. This creates both a further opportunity for car manufacturers to reduce the amount of time needed to charge the car and also for the suppliers to improve the efficiency of transferring the electricity.

In their accounts to 31 March 2016, Nissan Motor Manufacturing (UK) Limited stated £155 million R&D expenditure and Jaguar Land Rover Limited stated £1,242m of capitalised and £318m of revenue R&D expenditure. Both being categorised as “large companies” these figures would not have included the additional R&D undertaken by its contractors, so the actual expenditure these companies are already incurring on R&D would be much higher. Following this announcement, these companies, as well as Toyota Motor Manufacturing (UK) Limited, Lotus Cars Limited, and many others, will need to increase their R&D effort into the development of car batteries both in their charging time and performance.

This increase in base knowledge in the field of electrical engineering will eventually have further reaching value to other industries as other sectors will be able to benefit from the learnings from the appreciable improvements to the storage and generation of electrical power for electric vehicles and implement the advancements in other devices and settings.

Are we dreaming of an electric future?

The Global EV Outlook 2016 document highlighted that the cost of batteries has dropped from $1,000 in 2008 to $250 in 2015, commenting that this was due to research, development and demonstration (RD&D). Not only has the cost of batteries decreased but the improvements to battery density has led to manufacturers already being able to improve and increase driving ranges. However between now and 2040 this will have to be greatly improved upon for Britain to want to increase its 1.5% electric vehicle market share due to superior electric vehicle performance and not simply due to an imposed Government policy.

Furthermore, it’s not only the car manufacturers that will be looking at significantly increasing their R&D spend over the coming years in response to the proposal. According to the National Grid’s annual Future Energy Scenarios report, the increased number of electric vehicles on the road by 2050 is expected to increase the peak electricity demand to 85GigaWatt compared to 60GigaWatts today. In order to service this projected demand in electricity it’s estimated that the additional electricity needed is comparable to 10 times the output of the new Hinkley Point C nuclear power station or 10,000 wind turbines..

Clearly the construction of more nuclear power stations isn’t the answer; especially considering each station can cost £20 billion and take up to 20 years to build, for this reason new innovative means of generating electricity and power will have to be developed. Whether this takes the form of development into using a car’s own kinetic energy to power itself and other cars, increasing the amount of wattage generated from existing energy generating equipment like solar panels or wind turbines, or something not yet considered, innovative solutions will be required in the UK if we are to avoid having to import electricity.

The announcement will also have a knock on effect for companies like BP plc and Royal Dutch Shell plc. With the need and demand for petrol and diesel supplies in the UK significantly decreasing over the coming years, companies in the oil and gas exploration and production sector are going to have to explore and develop other forms of generating power, and profits, if they are to avoid a significant impact on their P&L, something that is inevitable.

The objective of the Government’s policy to tackle air pollution will directly stimulate research and development in multiple other sectors within the UK as they all look to react to either new revenue streams or improving the current state of knowledge and pushing the boundaries of what the UK consumer will expect from their vehicles.

With R&D activities anticipated to significantly increase across multiple sectors, the Chancellor’s assertions in the Spring Budget 2017 that the UK scheme was globally competitive will be put to the test as multiple multinational businesses will be ensuring that their development takes place in a jurisdiction that not only affords them the highest tax savings or credits but also provides the greatest certainty; an area that HMRC has already identified as something to be improved upon.

No Comments